Advocacy

We each have a vital role in identifying the social determinants of health and to use our voices from the frontline to help reduce the impacts of health inequalities for every child and young person we see in our clinical practice.

Creating equalities in child health

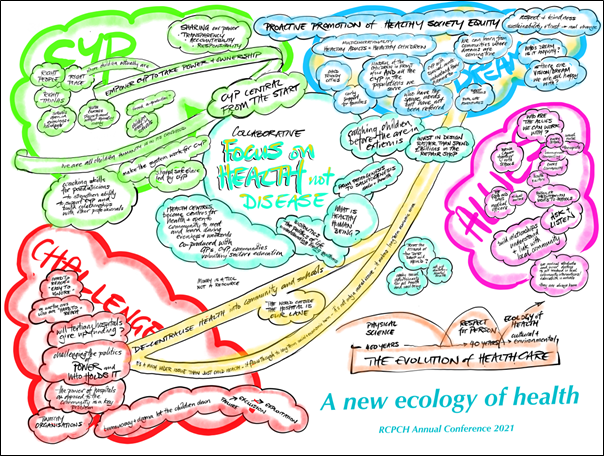

At RCPCH Conference Online 2021, expert panellists and young people across education, research, health and social care came together to discuss social determinants of children and young people’s health. We captured the responses of the panellists and identified 10 core objectives for child health professionals to address inequalities.

Foreword

For decades, there has been accumulating evidence demonstrating a link between societal inequalities and poor health outcomes in children and young people (CYP). The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all of us in so many ways and it has had a huge impact on many of the families and communities we work with. It has placed an unflinching spotlight on health inequalities and propelled discussions to the forefront, which highlight the urgent need for child health professionals and organisations to consider how ill health in CYP can be prevented as well as treated.

For many colleagues there is a sense of powerlessness. How can we have any impact in this area? What can we do as a profession? We find ourselves stretched clinically and having to manage so many demands on our time and resources.

At the RCPCH Conference Online 2021, expert panellists across education, research, and health and social care came together to discuss the role of child health professionals (including clinicians, practitioners, policy makers, and researchers) in improving health outcomes for children. In a session dedicated to the topic of the ‘Social Determinants of Children and Young People’s Health’, panellists reflected on their own observations in practice, and shared examples of interventions and tests of change to address the impact of health inequalities on the lives of children and young people in their communities.

These discussions were framed within the context of the evidence and methodologies generated through the Born in Bradford longitudinal birth cohort study and highlighted many current programmes of activity led by child health professionals across the UK and beyond, including ‘Connecting Care 4 Children’ and the ‘whole population’ model of care in North West London.

Our professional community have been able to find solutions to these complex issues using various methods, both small and large; applying co-production methodology, data integration and moving from research to active interventions to improve health outcomes for their communities.

We all have a role to play in contributing towards efforts to address the structural inequalities and non-communicable disease epidemic that affect children and young people today. Health and social care providers should be proactive in supporting efforts to reduce service demand rather than just responsive to the increasing pressures on frontline services.

In these discussions, the same core issues that need to be addressed were repeatedly identified, and compelling evidence was offered of tangible benefits for CYP and their families that can be generated through transformative interventions in local approaches to child health.

This page captures the responses of the panellists and makes for essential reading for all child health professionals dedicated to improving the physical and mental health of the next generation. A thematic analysis of the reflections provided by the panellists together with feedback from delegates attending the conference session and input from expert advisory groups resulted in the identification of ten core objectives to address inequalities as child health professionals.

This page outlines these principles and captures the insights and urgency of the conversation. There is a real sense of optimism and expectation and a feeling that we all can do something extraordinary when we work together with CYP and our communities at the centre. Most importantly, this page identifies case examples and actions that can be explored at pace by professionals if we are to tackle the growing health inequalities affecting the children and young people of today and in future generations to come.

A ‘Frontline Community of Practice’ (FCoP) is developing driven by peers within the Wellbeing and Health Action Movement network dedicated to building equality for children and young people. We capture the commitment of the FCoP to addressing child health equality below and share voices from the community to realise our shared vision.

Dr Camilla Kingdon

RCPCH President

Our commitments

Equality in child health is a central value of the RCPCH and our frontline community of practice

The RCPCH and our community will continue to support shared learning and research on new models of service delivery

The RCPCH and our community will champion the use of routine connected data (e.g. health, education, social care) to improve safeguarding decisions and improve children’s health outcomes

The RCPCH and our community will continue to act as advocates for the children and young people affected by the social structures that increase the CYP’s probability of experiencing poor physical and mental health

The RCPCH and our community will continue to encourage and support all paediatric services to engage in a meaningful manner with children and young people within their locality

The RCPCH and our community will investigate ways of facilitating interactions between schools and children’s health services

The RCPCH and our community will continue to advocate for children and young people’s voice and rights at local and central government

A shared vision

Health equality for children and young people

Becoming an advocate for equality so we are together for every child

- Fair outcomes for children and young people can only be achieved through health equality

- Health equality is created by building healthy communities

- Healthy communities require inclusive engagement of local talent and resourcefulness

Our vision can be realised through clear objectives and measurable goals. The realisation of these objectives can bring partners together across organisations in common purpose and generate the evidence needed to protect effective and sustainable investments in children and young people.

Health equality cannot be achieved through any single organisation and responsibility for delivery cannot be assigned to others. We need every individual with a duty for child health (from practitioners through researchers to policymakers) to take responsibility for driving the changes needed to increase equality.

Communities must be empowered through a whole system approach to driving equalities in child health and place-based collaboration that works to improve wellbeing and support the long-term physical and mental health of every child and young person. Local agency and power requires systemic structural, economic, environmental, and cultural equity.

A FCoP can facilitate the sharing of learning from hyperlocal demonstrations of improvement to enable a whole system approach that encourages celebration, trust, courage and joy in our communities.

We ask anyone with a duty for child health to join our children and young people’s health equality community of practice to help achieve our collective objectives.

Our frontline objectives

Promoting a shared vision of health equality for children and young people

The wellbeing of our children and young people is a barometer of the health of our society. Public programmes and policies must consider issues of childhood inequality, and act early to identify risk and mitigate adversity with meaningful interventions.

- Every member of the FCoP can commit to playing their role in delivering the RCPCH 2021-24 strategic commitment to addressing the inequality impacting the health of children and young people within the UK and beyond.

- We can work to develop an operational plan that can support services to work effectively together to deliver the vision of an equitable future for all CYP in our local communities.

- We can support the RCPCH to use its collective voice to ensure that the societal and economic benefits of investing in CYP are forefront and centre of local and central government policy.

- We can call on all organisations to tackle childhood inequalities as a priority with the commensurate broad and profound beneficial outcomes for the social determinants of health.

- We can work with the RCPCH and partner organisations to reflect our frontline voices in its advocacy for CYP and champion the prioritisation of children in discussions around the ‘levelling up’ agenda and recovery from the pandemic.

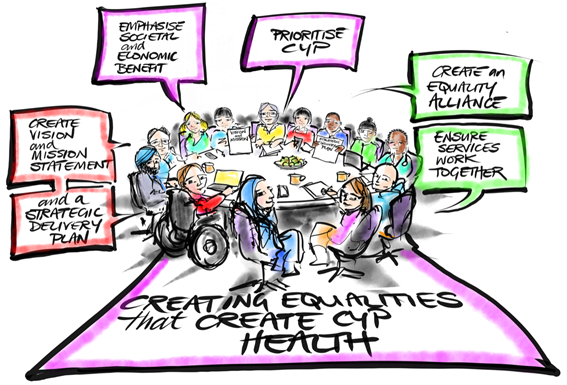

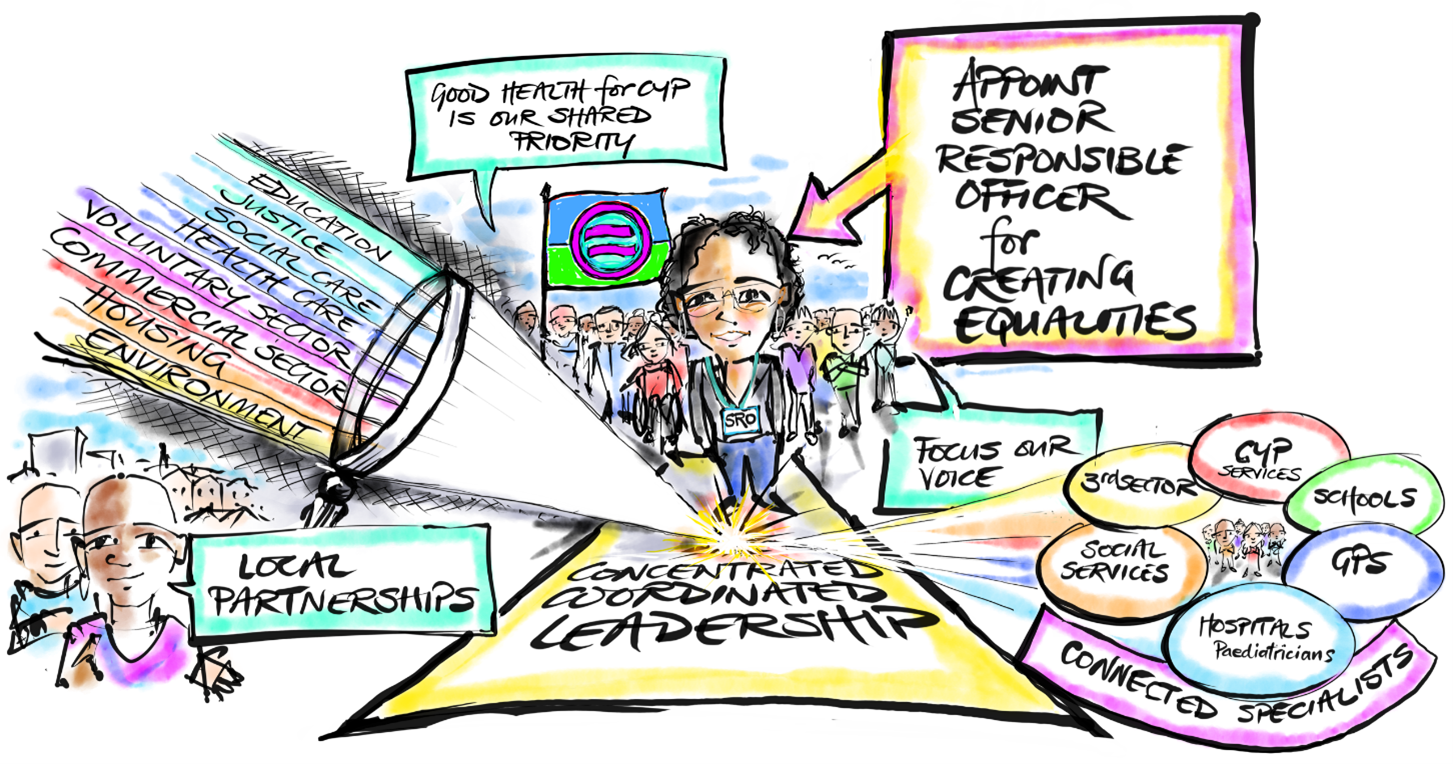

Campaigning for leadership dedicated to health equality for children and young people with coordinated service delivery

The health of children is affected by a myriad of factors requiring coordinated working across organisations (including education, justice, social care, the voluntary sector, and business etc). Concentrated leadership and multi-agency responses are required to avoid dilution of voice and fragmentation.

Individuals across different professions must be supported to work in harmony so that good health for CYP is a shared priority across sectors and organisations, including access to care in non-health settings, connecting with other agencies, and linking with other sectors (e.g. legal bodies and partners in the third sector).

- Our FCoP can advocate for Senior Responsible Officers to be appointed within local authority areas with the task of addressing childhood inequalities.

- We can help make the case for Senior Responsible Officers to have the permissions and mandate to act across all organisations in the best interests of CYP.

- We can support existing efforts to connect health and social care services, and encourage the inclusion of schools and those other relevant organisations who care for children and young people in the wider community.

- We can support the RCPCH in its advocacy for a designated Children and Young People’s Lead to be appointed within every Integrated Care System and/or commissioning body.

Encouraging a whole system approach to improving the health of children and young people

We must move away from a focus on treating health conditions in isolation. We need to adopt a whole system approach that considers the upstream determinants of health and wellbeing to ensure that families are supported, and the impact of health inequalities on children and young people is minimised. Child health professionals need to be able to work with multi-professional colleagues across primary care and the wider local community to create powerful individualised alliances for vulnerable families.

- Our FCoP can encourage health professionals to include questions on the family environment and social determinants of health in their consultations.

- We can support efforts to map all aspects of a child’s life so barriers to wellbeing can be better addressed within our communities (including food, warmth, shelter, domestic violence, mental health, education, role models, environmental and psychosocial hardship).

A focus on the populations and neighbourhoods disproportionately affected by medical and social challenges

The concept of proportional universalism should be championed within health and education services. The Department for Education’s Opportunity Area Scheme demonstrated what can be done when a ‘place-based’ approach is adopted within the most deprived localities, and when schools become hubs for tackling educational and health inequalities. A place-based approach allows a detailed understanding of a locality and a description of how different services intersect and interact (allowing the production of a ‘directory of services’). It enables a prioritisation of risks and interventions, and a method for developing comprehensive, reliable, scalable and fundable interventions with the community (using the assets and resourcefulness of the community, and building community leaders)

- Our FCoP can support the RCPCH to connect with national programmes of change to explore how health and education can be better integrated in the most disadvantaged areas.

- We can work with the RCPCH to promote the National Institute of Health Research funded Applied Research Collaborations as networks able to connect research and clinical efforts to tackle childhood inequalities.

- We can share learning from ‘Act Local’ initiatives that take a place-based approach to organising multi-agency responses for the most disadvantaged families (such as the work in Bradford led by the ‘Alliance for Life Chances’).

- We can help child health professionals contribute to descriptions of the assets (services, facilities, businesses etc.) in their local areas, ensuring that local services adopt a tailored approach to the context of ‘place’ and harness all available resources to create a coordinated approach to wellbeing for CYP.

Challenging our organisations – at every level – to take responsibility and be accountable for acting in the best interest of children

There is a need for local and central government to create strategic plans and a clear set of policies detailing how agencies can work together in the best interests of children and young people. We can support the RCPCH to work with partner agencies, key stakeholders, and capture the voice of children and young people to create a commitment to building a fairer society and creating a proactive health system.

- Our FCoP can use its membership to help RCPCH operationalise its social values (as outlined in the 2021-24 strategy) and challenge our national and international institutions to use research and data to tackle the social determinants of health.

- We can work with the RCPCH to connect anchor institutions and share learning from the many isolated examples of innovative approaches.

- We can encourage greater coordination of equality building activity between organisations, and challenge organisations that fall short.

- We can amplify the voice of the RCPCH and promote access to information on creating equality, facilitate conversations, coordinate actions, and articulate the importance of addressing structural inequalities.

Advocacy for children and young people and promotion of proportional universalism

Any professional with a responsibility for children and young people should be an advocate, committed to decreasing inequality and promoting proportional universalism. Child health professionals need to be supported to understand and address the complex dynamic systems that surround a child and ensure these wider determinants influence how services are delivered for families.

- Our FCoP can support healthcare professionals who wish to be an important voice and advocate for disadvantaged families within their communities.

- We can share ideas, expertise, experience, and learning from local interventions tackling inequality.

- We can disseminate evidence-based approaches adopted within other societies and countries, and from research programmes (such as the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, and Born in Bradford)

- We can work with the RCPCH to support shared learning across our community through network meetings and shared online resources containing practical tools and a repository for information with case examples of good practice.

Partnership working with local communities to improve health outcomes

Communities need to be at the centre of service delivery design that crosses organisational boundaries. Communities need to be at the heart of efforts to drive forward solutions (such as peer-to-peer networks). Families can provide essential information on the challenges to healthy lives within communities, and extraordinary results can be achieved in improving health outcomes when CYP and communities become involved. There is a need to simplify the complex systems that families must negotiate to get the care they need. This can only be achieved through partnership working within a ‘whole system’ approach that is fully engaged with the key influencers within the communities.

- Our FCoP can seek to influence national and international programmes of improvement in place-based working.

- We can collate information on effective ‘community engagement’ approaches within other areas, and help members apply the learning within their own locality.

- We can help child health professionals work with their communities to create systems centred on children and young people.

- We can share ‘toolkits’ to help health service providers in each locality establish CYP and family forums to help shape their policies and decisions.

Supporting the use of education in the fight against inequality, and helping empower children to tackle the wider determinants of health

Many child health professionals are managing multiple demands on their time and resources, and have a sense of powerlessness regarding their ability to address social determinants of health. Training for child health professionals to understand wider health determinants and ideas on how to tackle these issues locally would be invaluable.

- Our FCoP can support the RCPCH in its work to ensure paediatric education and training across all specialties includes information on the impact of social determinants of health, and provide case studies and learning to support the launch of Progress+.

- We can support the RCPCH to train paediatricians and child health professional colleagues as local communicators and advocates for child health, utilising existing initiatives such as the RCPCH Ambassadors Programme.

- We can aim to strengthen health professionals’ confidence and ability to speak in a simple and powerful way about health inequalities, and build the relationships they need with other professionals in their local areas.

Exploring how health professionals can work more closely with schools and nurseries in local areas

Many schools want to work with health providers and support local centres for child health and wellbeing. Ensuring a school nurse is available for every school, schools can also help child health practitioners to understand the social needs of the children that come to the clinics and hospitals. The realisation of this partnership working requires improved information sharing between health and education.

- Our FCoP can help accelerate connections between the RCPCH, the Department of Health and Social Care and Department of Education to help coordinate partnership working across health and education.

- We can help co-produce approaches to childhood health and wellbeing within the context of educational settings.

- We can support child health professionals to work with schools and identify opportunities to educate and empower CYP on health improvement in their local communities.

Championing efforts to make routinely connected data available to practitioners who care for children and young people

There is an urgent need for high quality, local data to be made available and used to target resources and avoid the unwanted consequences of increasing inequality. The support of vulnerable children requires the development of tools that can identify need early and support practitioners to work in a genuinely multi-agency manner.

- Our FCoP can add our voice to national demands that local authorities connect with health providers and generate learning through the use of connected routine datasets (including health, education, social care etc) within service delivery.

- We can provide powerful examples that our members can draw upon when advocating locally for the digital resources that enable them to better identify risk and organise support in an effective multi-agency manner.

- We can support the RCPCH to represent children and young people within national data improvement groups, and advocate for a focus on decreasing inequalities through the improved use of data and tackling the problems created through a lack of information sharing.

- Our FCoP should communicate examples of good practice in data sharing – such as the DATA 1 (Digitally Acting Together As One) programme within Bradford.

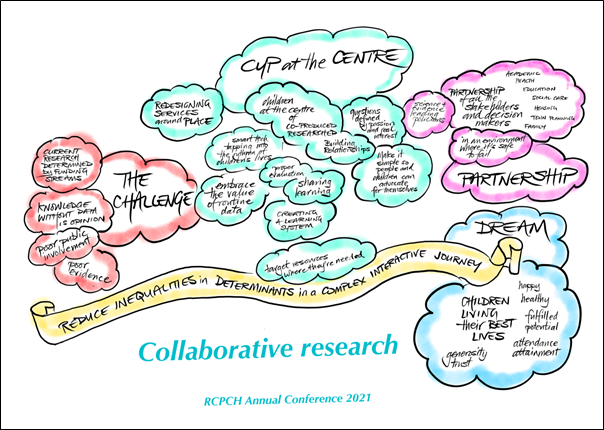

Research that can change children’s health outcomes

Born in Bradford: Can a research project change a city?

Born in Bradford (BiB) is an internationally recognised research programme which aims to find out what keeps families healthy and happy. We use this information to work with the local authority, health, education and voluntary sector providers across Bradford district to develop, implement and evaluate ambitious programmes to improve population health. We have a vast ‘city of research’ infrastructure that includes detailed health and wellbeing information on Bradfordians enrolled in our three birth cohort studies first established in 2007, connecting a routine dataset of health, social care and education data for over 700,000 citizens (16,000 families) living in Bradford and Airedale. We host a range of initiatives to improve health working with the local authority, health, education, cultural and voluntary sector providers. BiB’s goal is to produce ‘research that changes a city’.

Our rich research infrastructure allows study of the interplay of deprivation, ethnicity, migration and cultural characteristics, and their relationship to health and wellbeing outcomes, with relevance to communities across the world. Our evidence has highlighted the pernicious impact that deprivation has on the health and happiness of families and the inequalities at play in our society. It has highlighted the importance of early intervention, both to prevent ill health, and promote opportunity and prosperity across the life-course.

It has also highlighted the need for a systems approach to thinking about how to prevent ill-health, moving away from a biomedical, individual approach to understanding how the areas in which we live and the circumstances in which we grow up have a key influence on our changes of staying health, and achieving our potential. For children living in deprived areas, a whole raft of environmental (e.g. lack of green space, pollution), economic (e.g. financial insecurity, employment prospects) and social factors (e.g. high crime rates, poorer performing schools) create a vicious circle leading to ill health. If we are to develop a more holistic approach to health then we need to understand and address these wider influences.

Unfortunately, prevention intervention at this systems level is still chronically underfunded in the UK. Our mission within BiB has been to use our findings to advocate for change, and to provide a model for how we can embed research within practice. BiB research has led directly to major investment in child health interventions in the city, including Better Start Bradford, the Bradford Opportunity Area, a Sport England local delivery pilot, Arts Council projects and a Bradford Clean Air Zone. Examples of BiB’s research impact on clinical, educational and social policy include; establishment of a regional congenital anomalies register, early life interventions for obesity prevention and physical activity, the redesign of mental health services to improve detection and support for children with autism, changes to school admission policy for children born prematurely, and the design and evaluation of an ambitious clean air zone.

Prof Rosie McEachan, Director of Born in Bradford

Prof John Wright, Chief Investigator Born in Bradford

“I worked in paediatrics when I was younger and my first link into research was a study on meningitis in children in Southern Africa. Over the last 15 years, we have been running Born in Bradford and you get to a stage where you find the epidemiological evidence is just repeatedly describing the problem – a problem that is deeply rooted in inequalities.

So, in recent years we have moved our focus to trying to address these health inequalities by taking a whole city and system-wide approach. Our ActEarly City Collaboratory aims to harness strong community co-production, the richness of our linked public datasets and a critical mass of prevention interventions. Key to this aim is the move into communities and local government – helping to embed research and science into everyday policy and practice.”

Prof John Wright

Director of the Bradford Institute for Health Research and founder of ‘Born in Bradford’.

Co-director of ‘ActEarly’ – a whole systems City Collaboratory approach to improving the health and life chances of children from deprived communities in London and Yorkshire

“Without data, I’m just somebody else with an opinion. COVID-19 has shown us how limited our current national data collections are. We could not readily identify those children and young people who we felt at the start of the pandemic might be most at risk, and we must do much better for our children.

We know that these determinants are not evenly distributed across the country and we need high quality local data to be able to target resources where needed, and work with the local communities to ensure those interventions are acceptable to that population. Without that high quality local data collection, there is a real risk that blanket public health or other service redesigns that are designed for the majority can actually result in increasing inequality and make things worse for these children. Children don’t live in healthcare systems and we need to understand all of their lives to understand their health outcomes – that’s not just health, education and social care, but also their families, and we need to be better at linking these data together.

COVID-19 has shown us that we can do that and broken down some of the existing barriers that were there, and I’m hoping that continues beyond the pandemic. It’s also really important to understand that data is not just there to identify problems, but they can also help us evaluate interventions in service redesigns. By evaluating, we then get the opportunity to share learning with other regions of the UK, which is again something that we don’t do as well as we could do.

I think we have a real opportunity to improve data collection and linking data across sectors so that clinicians on the ground, including trainees, managers, service providers, Commissioners, and policymakers, can all understand the role in the value of these data and in collecting data well. You need the resources in order to do that and to utilise these datasets. Data can save children’s lives if we use it properly.”

Prof Lorna Fraser

Professor of Epidemiology at University of York

With a background in clinical paediatrics, Lorna’s research interests are in paediatric epidemiology with a focus on chronic disease and life-limiting conditions in children, spatial analyses and equal access to services for children and young people.

“I want to look at research and how it can change outcomes and I want to consider research as coming up with questions, during the process itself and then the final part, which to me is the most exciting part: How do we take that research and make it do something and actually achieve something?

I think if we look at how we currently find questions, we’d like to think that you see a problem and subsequently you ask a question to explore that issue and you start the research there. However, we all know that research is largely dictated by funding streams and the PhD students go where the expertise already is. So, where there’s a Professor already doing work in an area, you will work on their topics. We have these amazing centres that have done so much work in these hyper-specialised areas, but how do we fill the gaps in between? As individuals we will instinctively work on questions that are familiar to us on topics that we are passionate about. One of the ways I think we can do better research for children is by considering the person doing the work and the way the person comes into this. How can we make sure that the researchers are as diverse as the populations they’re trying to work for/with; so that they can actually relate to the problems and understand the context successfully, which is why stakeholder mapping is critical at the start. How can questions be shaped by the clinicians on the front lines, who potentially don’t have the time to do the research that we need to answer these questions; and how could it be shaped by children and young people themselves? That way if they are experiencing something, they can see that reflected back in the work done by the professionals around them.

Just as for many children and young person, for me it was a terrifying process to consider being a part of research itself. When I was at Birmingham Children’s Hospital, their motto was ‘every child through research’ and that mindset entirely changed how accessible participating in research felt – the norm. Everybody was going to be approached and often worked to develop the participant leaflets for studies that would benefit them. Every child might not be in a recent study, but we do want it to be normalised and we want it to be accessible. The processes by which we currently do research need to be co-produced or developed alongside young people or people that are closely affected, their families and their carers. Quantitative data is so helpful, but where I’ve seen the biggest impact is where we can describe the problems and high-quality qualitative research that says why, that truly asks why, and listens to the people that are most affected by the issue in question – this is the most impactful because it gives us a narrative by which to drive change.

I sit in the Children and Young People’s Programme at NHS England which is an enormous privilege as I get to work with amazing charities, clinicians and across government but what I’ve reflected on is that the processes a lot of us imagine from research and evidence-based policy is probably not as clear as we’d like. A lot of it is dependent on the access and the evidence that the policymakers have themselves. So, I think from a research and academic perspective, how are you building those relationships and making sure your findings are really easily usable, and particularly for young people, how are you making sure that the findings that you have are processed so they can understand them in response to a question or problem that they’re facing, and that they can use? Because it is so gratifying seeing an experience that you’ve struggled with and tried to articulate, validated by evidence and by research. I think the hurdle of getting to publication, particularly as that is the metric by which many teams are funded, can be so difficult that we stop at the part where we connect with people who work in policy and actually break down what we worked on for years into really easy digestible bite sized pieces.

If we consider the climate, the way that young people are able to advocate around the climate crisis is because the climate scientists have spent so long trying to make us all understand in really simple terms what is happening to our planet and steps we can take to remedy this. This has been done in such a way that we young people can understand it and importantly use that information to advocate for ourselves. I think until we do that in health, we won’t be able to see these changes because the problems are too big for us to explain and it definitely cannot be done by using the language that research is using. If we put the beneficiaries of our work at the heart of each step of research we’d not just have better outcomes but we’d enable children and young people to own the solutions or next steps alongside the system.”

Gabrielle Mathews

Medical Student at Imperial College London and winner of the Diana Award for inspiring positive change in the lives of young people

Youth Expert Advisor, Children and Young People’s Transformation Programme and youngest member of NHS Assembly – NHS England and NHS Improvement

Oversight board member of the REAL Centre at The Health Foundation, #iwill ambassador and youth representative to BackYouthAlliance

“I’m a respiratory paediatrician and what I see in my clinic and on my ward rounds is not really a set of lungs – it is a set of lungs on a journey from 4 weeks post conception, right through to adulthood. I’m very aware of that and a lot of the determinants of health that we think about that affect those lungs are there and then, and some of them are later on in life. It’s very clear to us that those determinants don’t happen in isolation. They happen in a complex interplay of factors ranging from air pollution, maternal health, maternal stress, food, schools, exercise, and obesity, race, gender – all of these things lead into how someone’s lungs are right the way through that journey.

That’s why isolated bits of data don’t really help us, we need a combination of quantitative and qualitative data, and those data need to be collected and connected. One of the great things about Born in Bradford, I think over the years, having watched it progress on its own journey, has been the ability to link data and look at things in a far more sophisticated way. For me, I think the next step is how do we link between health and non-health? We work with children because we want children to live their best lives and if we want data to help that then we need to be tapping into the rhythms of those children’s lives.

Luckily most children don’t spend all their time in healthcare institutions, so we need to be looking a little bit wider, for example at schools. Schools offer both threats and opportunities for child health. We’ve seen this year how healthy children can be if they are not exposed to the usual viral milieu at schools, we’ve seen a drop in our asthma admission rates. So schools offer an important part of the data that’s missing. If we really want to know who has got asthma, we should be speaking to PE teachers, not respiratory paediatricians. We need to be really linking into the data that we have out there in the community.

We know that school attainment and school attendance are two really important parts of life and opportunity. We can start to link between health and schools and then even further – smart technology has been great at linking in with peoples’ minute-by-minute lives, and it all comes back to that idea of tapping into the rhythms of children’s lives. The only way you can do that is with sophisticated data connection and programmes like Born in Bradford are giving us a great opportunity to move forward in that sphere.”

Prof Ian Sinha

Professor in Paediatric Respiratory Disease, Alder Hey Children’s Hospital

University of Liverpool

“I think the use of information created by the interaction of the public with public services to make services better is hugely underdeveloped and needs to be more developed because there are still large areas of care, particular primary care and children’s social care that are substantially “evidence free” zones. In the minority of cases where interventions have some evidential basis, that evidence is generally weak. Places like Bradford have shown us how routine data could make things better by providing the basis for a whole population prospective observational study that will allow us to look at questions both of the social distribution of needs, the use of services in relation to these needs and the inequalities this frequently highlights. Real world evaluation of the effectiveness and the value of those interventions that can be identified in routine data can also be enhanced by embedding research studies within these data resources.

The necessary infrastructure at a national level to support this is currently in a very nascent form. COVID-19 has accelerated the development of several national data assets and mechanisms to access these but still these collections mainly consist of primary health care data linked to relatively limited secondary care data. In several regions like Bristol, Bradford and Liverpool, we are trying to do things locally that are perhaps easier to achieve than nationally. In Bristol, we collect data from multiple agencies, across social care, education, criminal justice, employment and benefits and health, and integrate these data to inform resource allocation according to need and target interventions. There are valid concerns that screening interventions may do harm, because they have false positives and false negatives and potentially expose people to ineffective interventions and stigma, but some screening interventions can also do good through identifying need and giving people access to effective interventions that they would otherwise not have received. The challenge is always to evaluate as rigorously as we can, and to assess where we are on that balance between good and harm in relation to any intervention.”

Dr John Macleod

General Practitioner and Co-lead for the Centre for Academic Primary Care and the NIHR School for Primary Care Research at the University of Bristol

Director of NIHR ARC West and lead for Applied Health Informatics for the national ARC network.

“The single biggest change that I would advise to make is to work as a partnership. Underneath that lies everything else and its key feature is working together committed to a unifying vision. It’s taken us 10 years but we now have a very strong local partnership that is committed to a single vision and agreed purposes. Our partnerships are composed of the right people in the right place who care about the right things; so we’re all in it together. It’s very important that the right people are around the table, including the decision makers who can make things happen alongside the crucial participation of the people and patients directly involved to ensure children and families are absolutely core. Leadership in my view has to be clinical and academic. It has to come from people who genuinely know about what the problems are with the knowledge about how to make things better.

We have a partnership approach with a clinical academic ethos running through it. All this rests on a learning health system platform. This means that what underpins all our work is collecting data meaningfully for clinical and other decision makers to bring benefit directly to patients and populations, and to researchers so that the evidence base can be strengthened. This clinical-academic approach runs through the entire thing. The partnership that I direct is about health systems strengthening and creating a learning health system. The visible deliverable is a new model of care – integrated care that is proactive, and effectively delivers early intervention and biopsychosocial care. We use data to find children who are at risk of a particular issue and scoop them up early, and we use data to adjust the system to meet needs by area so more intensive services are available in neighbourhoods with higher needs.

The next step is to apply these tools and methods to other conditions and risk factors. One important aspect of all this is the way that we evaluate and we’ve developed a pragmatic model that is rigorous at running simultaneous service evaluations, because we need to be able to speak to the management and the Commissioners as researchers much more eloquently than we have done traditionally, alongside a randomised controlled trial that also adds to the evidence base. Hopefully we will end up with better funding models for pragmatic and rigorous research, so the approach can become easier and more embedded.

The net effect of all this is that we can improve health, both in measurable health outcomes and healthcare quality, and reduce acute service demand. Cost-effectiveness is the crucial decision-making point, but best of all it also reduces inequality in access to care through the smart use of data. It has shown that we can improve population health and reduce inequalities through NHS action in conjunction with actions on economic and social determinants of health.

So how do you combine paediatrics and public health? Could you actually help in service delivery through using population health knowledge, tools, and methods? In effect this is about the NHS’s role in health promotion, effective care for populations as well as patients and inequality reduction. The service needs to become proactive and able to reach out to the community, not just by relocating services well but proactively engaging with children in the community, identifying risk early and delivering early intervention in a meaningful way. A proportionate universalist approach to health, that encompasses health promotion and healthcare is what we need to aim for, and it should be integral not an add-on done only by other people. This approach can be part of everyone’s work – it’s more than just making every contact count, it’s about how we plan and deliver care as a system, looking after populations before they become patients.”

Prof Ingrid Wolfe

Consultant in Child Public Health at Evelina London Children’s Healthcare and Clinical Senior Lecturer in Child Public Health at the School of Population Health Science, King’s College London.

Director of Children and Young People’s Health Partnership in Lambeth and Southwark and co-Chair of the British Association for Child and Adolescent Public Health.

“What can we do within our own services to make sure that we’re delivering them in a way which mitigates health inequalities and addresses some of those structural barriers to good health outcomes, rather than inadvertently exacerbating them? What can we do as individuals to really influence decisions around the social determinants of health that have such an important influence on our patients’ lives?

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recently published the first guideline for improving the patient experience of babies, children and young people receiving NHS care. Evidence shows that a positive experience of services is important for engaging people with their own health and ensuring adherence and future engagement with health services. All the young people on our guideline development panel talked about how a dismissive comment, being made to feel unwelcome, or not feeling listened to had stayed with them – it wasn’t just an isolated incident that the professional might forget but something that was on their mind the next time they were thinking of calling their GP, the next time they were thinking about seeking help, how they were dealing with transition, and often years later.

We need to consider how we can build on those relationships that we’ve developed during the COVID-19 era. How do we strengthen our relationship with colleagues in education? How can we advocate as a collective voice to make sure children and young people really are at the centre of policy as we try and come back from the pandemic?”

Dr Dougal Hargreaves

Honorary Consultant Paediatrician at University College London

Research analyst at the Nuffield Trust and Clinical Senior Lecturer at Imperial College London

“When we were selecting indicators for the State of Child Health report, there was some anxiety about including indicators that were not directly related to health and healthcare, but we know factors outside healthcare have an impact on the health and well-being of children and young people. Of course we focus on healthcare, but that’s not at the exclusion of other professionals also involved in the wellbeing of children and young people. We need to work with our colleagues both at an individual and collective level – that idea around doing it as practitioners and then also as a system is a really vital model of thinking.

There are 3 areas in which we can help take this forward. The first is around policy influence and the RCPCH has been doing significant amounts of work on this for a while. Strengthening those links, particularly with other sectors such as education is critical. The second is driving changes in practice. How do we facilitate healthcare professionals to practice in a way that can address inequality? Sometimes you feel disempowered as a frontline clinician when we think about topics like poverty and inequality. How can we create structures to help clinicians link this awareness tangibly into their day-to-day practice? The third is thinking about the next generation of paediatricians. How do we embed this way of thinking into all of our training and education curricula?

We’ve moved on quite a lot over the past few decades from thinking about healthcare as a snapshot, thinking about it as a single episode, towards thinking about the life course approach – and that’s now completely permeated our thinking across paediatrics and also more broadly in medicine. Let’s extend that lens even more, and start to move from episodic to longitudinal, and further towards depth. The underlying factors whose clinical manifestations are just the tip of the iceberg, and which require tackling at source or else the health effects will never improve.

In paediatrics, we have increasingly led the way in thinking about inequalities in healthcare and social determinants of health for a long time. We’ve seen the National Institute for Health Protection take the reduction of health inequalities on as a priority, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence tackle inequality as one of the five pillars in their new strategy.

In its own way, this approach is for everyone and something that we should all be involved in. In clinical practice, lots of colleagues both trainees and consultants, will say; “but what can I actually do about this? How can I take this forward?” We need to coalesce together and show each other that it is feasible and possible, and we need to break that down into practical steps. The State of Child Health report includes at the end of each indicator a specific set of action points for clinicians to take forward – at the service level and at the wider societal level.”

Dr Ronny Cheung

Consultant and joint Head of Service for General Paediatrics, Evelina London Children’s Hospital

Clinical Director of Healthy London Partnership’s Child Death Review Transformation Programme and Co-author of the State of Child Health Report

"If we put the beneficiaries of our work at the heart of each step of research, we'd not just have better outcomes but we'd enable children and young people to own the solutions or next steps alongside the system"

Co-producing solutions to health inequalities

“The “world of our dreams” is a world we would all like to create for our children. It’s a utopia, a world where there is freedom from the fear of injustice and inequalities for children. It is a world of healthy environments and equality. But it’s worth asking: Whose dream is this? Is this our dream, is this the dream that children and young people have described? Is this the dream of our politicians? Is this what teachers want for children? What local authorities think about as they’re commissioning services?

Every time we think about co-producing research and policy solutions, we need to think about who we are engaging in the process, and all the different levels at which we want to engage people. We can go to international organisations, such as UNICEF, for example, and see what they think should be done for children – they have a vision of Child Friendly Cities. If we look at city regions, cities and local authorities, we’ll find many different visions of what children’s worlds should be like. Neighbourhoods and local communities would envision a ‘world of our dreams’ differently – and this would be true of different schools, different families and for individual children and young people. When we aim for meaningful co-production, we really need to think about how we work across those levels and think about whose voices we are hearing.

At Born in Bradford, we’re currently working with young people as we prepare to study their health and wellbeing through adolescence and into adulthood. We’re starting to ask them how they would like us to ask them about their gender identity and their sexual orientation, how we should measure difficult issues like bullying and cyber bullying, drug use, or street violence, but also about the positive things they do such as sports, volunteering and engagement in the arts. Sometimes we find that the words we researchers would use are very different to the words young people would like us to use; sometimes we have very different ideas about what is important. It’s an essential step in us creating research that is inclusive and meaningful to participants, even if it takes time and resources and can be challenging. This kind of co-production is necessary if we’re going to be able to use our research to help create a “world of dreams” that children and young people actually want.

We have to make sure it’s their dream too and then we have to make sure that that dream can be something that policymakers and politicians will also take on board and help us to bring about. Utopian worlds and worlds of our dreams that we’re all striving towards can feel discouraging if we’re aiming for something that seems too perfect, too unattainable. But in creating scenarios that are a vision for a future based on bringing together elements that are all actually happening somewhere in the world: the utopian vision is built up of real-world practices and policies. It shows people that what they dream of can be achievable – there are places that strive to do all of the things we want for our children, and we can help to make it happen in own communities too.

We need to build partnerships across different sectors – communicating across different sectors and different institutions, learning each other’s language, hearing each other, and acting as allies is vital as we all work towards improving children’s worlds. We need to make sure that we all use this moment to really focus on children, their lives and their life trajectories. And that we do everything we can – in partnership – to achieve a “world of dreams” for children.”

Prof Kate Pickett

Professor of Epidemiology and Deputy Director of the Centre for Future Health at the University of York

“I have been working to reduce health and education inequalities in the Bradford District since the 1970’s. That was a decade when health initiatives were focussed on enabling people to access information, using a patriarchal and homogenous approach to the health of minoritized communities, leaving behind a lack of evidence of the effectiveness of these very disparate short-term initiatives. The health systems at that time, and continuing into the 1990’s, were set up and funded using a competitive model, far from the collaborations with the voluntary, public and private or business sectors we see today.

We need to learn to look at cross-agency working through a different lens, that of the people in our communities who continue to experience health inequalities. Health inequalities can be avoidable but dependant on socioeconomic factors, the geography of where we live, our protected characteristic, our level of education – the lack of equity, in not just health but in education and employment. What have we learnt from the past, how does this inform our approach today and does this really address health inequalities? Are we really spending enough time with the people that we are meant to be serving and supporting? The only way to hear and act on the voices of our communities is to re-examine who we think the stakeholders in effective collaboration are.

One example is the ‘Glasses for Classes’ initiative where a child will have their eyes tested in school. As a result of collaboration between the school, parents and carers, clinicians, and other professionals, the child receives a one-stop service in school and two pairs of glasses -one for home and one kept at school. Understanding what simple but effective interventions are needed to provide a seamless service to our families is essential. Similar initiatives have been developed around dentistry and autism – data across education and health is shared, and evidenced-based research leads to initiatives that work by demonstrating how analyses of different data sets enables sustained approaches to sustained interventions.

The importance of collaboration is it helps us challenge concepts like the assumption that people impacted by health inequalities are coming from ‘hard to reach’ communities. It is us, the new ‘gate keepers’ and agencies, who are hard to reach in thinking we hold all the solutions to inequalities. We must continue to build trust with the communities we serve and make sure we learn to communicate and understand the lives of our communities. There’s a lot we don’t see any more and we cannot be complacent; we must continue to challenge ourselves and each other if we seek to finally end the health inequalities experienced by our communities and move to a position of equity and social justice.”

Dr Nadira Mirza

Deputy Chair at Airedale NHS Foundation Trust

Dean of the School of Lifelong Education and Development at the University of Bradford

“Prof Neil Small at the Health Research Faculty of Health Studies, University of Bradford once said “those in power or with high status need to separate from the powerful and make alliances with the less powerful.” The only way we can achieve top-down measures is to begin by demanding greater scrutiny, transparency and above all, accountability. Not only this, but a fairer distribution of power to include service users in the decision-making.

During the pandemic, we witnessed many ‘pop-up’ organisations, from government level to local level, setting up within earshot of news of funding availability. I call these organisations ‘funding-chasers’. Though this has been happening for many years it took a pandemic to highlight this matter. These organisations have had access to funding, because of who they knew not what they know of the service they are pledging to deliver.

Then there are community interest companies that are created to match the funding criteria and not necessarily focusing on the intervention that is required, in communities desperate for change. These organisations often have little experience or knowledge of the field that they are proposing to engage in. Funders have a responsibility to promote co-production and design of an intervention. This will allow service users to feel they have been heard, and funding bodies can justifiably help the community reach its potential, through openness, accountability, fairer distribution of power and above all financially supporting those organisations with a greater know-how.”

Tahira Amin

Managing Director of Abilities Together, Bradford

“I distinctly remember someone saying to me; ‘hard to reach’ communities are not hard to reach, just easier to ignore. By being innovative we can reach communities that need to be heard and engaged, and when developing these approaches, we also need to work in partnership with the young person rather than above them. As a young person myself, I can tell you that by doing this we feel empowered and we have permission to help you develop these approaches. This means whatever you are doing will be far more effective and young people will feel they have the power to express their actual views, which is what we’re wanting when addressing inequalities.

As Chair of the National Network of Youth Forums, a great way of engaging sustainably with children and young people, is a youth forum. There has been amazing work done up and down the country by local Trusts and Health Boards co-producing with young people to ensure healthcare services within their area are fit for purpose. So if a Trust or Health Board hasn’t got a youth forum, what are you waiting for? Start setting them up!”

Haris Sultan

Founder and Chair of the Youth Voice Assembly

Member of the National NHS Youth Forum

Co-founder of Leeds Community Healthcare Trust Youth Board

“I’m in Cincinnati and we have a large Children’s Hospital that’s taken on population health as part of its mission, trying to follow the rhythm of children’s and families’ lives to understand where help is needed. We’ve had some significant achievements along the way including dramatic reductions in extreme preterm birth and a 20% reduction in paediatric admissions in some of our hardest hit neighbourhoods. We’ve also been supporting our urban school district, where some of the children at highest risk go, to close equity gaps in academic outcomes.

We’ve tried to figure out how to take what has worked in healthcare quality improvement and adapt Deming principles to improve health not just healthcare, and make those methods accessible to our community partners and families themselves so that we can all be better at what we do every day to support vulnerable children and young people. We are focused on family-centred design methods as a way to address the complex array of factors that affect child health and development. Using QI and design methods, we’ve built an open learning network in the community that’s intervention oriented.

My top three collaborators, where all my email comes from, are school leaders, legal advocates working for children, and child welfare system collaborators – we’re all trying to figure out how to work effectively for true impact. If I were to distil 4 key pieces of what’s worked for us here, the first would be developing an unassailable, measurable goal – one that no single sector alone can take on. That’s very uncomfortable; it creates a lot of fear but when you put up a high enough goal, with enough urgency behind it, you get a coalition of the willing drawn from all sectors.

The second element is putting children, young people and their families at the centre. It’s such a complex system, we are all seeing it from our own silos, but the families are on that journey and following that rhythm, and they’ll be the first to tell you where the breakdowns are between systems and sectors. They’ll help you build a better theory that is co-produced with them, and they’ll tell you what and where the interventions should be.

The third element is working hard to create the right environment; not one that is fail safe, but one in which it’s safe to fail. For example, starting small enough when the issues are this complex that failure is a chance to learn. People can be afraid to try something different for fear of failure and judgment by others, but by creating an environment of small-scale testing – e.g. following one family, then five, then 25 – one can break through this fear.

The final element is reflecting on what it takes for us to be trustworthy. We have a lot of families who appreciate the wisdom of the healthcare system, but then it’s really about what Grandma says or what Auntie says. So, what can we do to be truly trustworthy, to be generous, and to bring a sense of urgency to the important child health issue?”

Prof Robert Kahn

Professor of Pediatrics and Associate Chair for Community Health

Executive Lead, Community & Population Health at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

“I have been a Consultant Paediatrician in Leeds for 25 years, working in both General Paediatrics and sub-specialty Children and Young People’s Diabetes care. Inequality in healthcare has always struck me as something that we know about, we read about, we want to do something about, but we are not entirely sure how to go about fixing the problem.

The most important thing is to go back to our vision for healthcare and involve young people in the dialogue from the start. I believe very much in working in partnership with young people and involving them in the development and shape of a healthcare service that appeals to them, because we think we might know what is acceptable to young people, but we don’t know unless we ask them. We must listen to their voices, understand what they are asking for and try to put their ideas into actions.

And it’s important we listen to as many diverse groups of young people and their families as we can. We must involve people from all our varied communities in discussions and get a better understanding of their experiences of health and healthcare. In my own clinical area of interest in diabetes, there are communities that hold the belief that diabetes can be cured by herbal remedies. This is not a view held by the professionals so how do we overcome these differences and seek out ways of approaching self-management advice that is acceptable and doesn’t lead to poorer outcomes for these groups in society? In order to address inequalities we have to make every effort to understand the points of view of all people making up our diverse communities.

I’m a big believer in peer networks. Gathering together young people with similar backgrounds, similar understandings, perhaps similar language, and giving them the opportunity to express their views as a collective and not just as individuals is very powerful as we know some young people simply don’t have the confidence to express their voice independently. They become much braver in expressing their opinion if supported to do so by peers. Giving them this opportunity means that they are not held back in any way from telling us their opinion on the models of healthcare that they believe they should receive.

We must be highly motivated, have a positive mindset and believe that we can make a difference by sharing our ideas. We need to build on momentum that is behind the health inequalities agenda to really try and make a measurable difference to children, young people and their families, and our schools are absolutely fundamental in helping us achieve what we would like to see going forward.”

Dr Fiona Campbell

Consultant Paediatrician and Diabetologist at Leeds Children’s Hospital

Chair of the National Children’s Diabetes Network

“I moved to GP training from paediatrics after completing my membership for many reasons, including the desire to walk with someone through their health journey and primary care at its best is able to that. One of the biggest differences I’ve noticed working as a GP was that it feels much more isolated than working as a hospital doctor. Overcoming this is something that I’ve deliberately worked at, and the working relationships I formed during my training have continued to be really useful. It is giving me opportunities to conduct initial health assessments for looked after children and unaccompanied child asylum seekers, start-up outreach clinics to children in temporary accommodation and develop training opportunities for new GP trainees. In Bradford, GP trainees work with the hospital paediatrics ambulatory care team concentrating on service development and quality improvement. There are many GPs like me with a passion for paediatrics and we need to be encouraged, released and supported in working at greater depths.

Isolation felt like an issue for me, but how much more must my vulnerable migrants and homeless patients feel isolated. Since 2017, there’s been obligatory upfront charging for undocumented migrants in hospitals and community health services with some exceptions. Charges must be paid before treatment unless it’s assessed to be urgent or immediately necessary. Rights to NHS treatment for overseas visitors are difficult to understand and results in unnecessary barriers. Much of my work is advocacy and bringing down these barriers. Get to know your local GPs and GP trainees, and be open to opportunities to work together to put the child and family first rather than remaining mired in our traditional rivalries or overwhelming bureaucracy.”

Dr Jess Keeble

General Practitioner at Bevan Healthcare in Bradford

Training Programme Director for the Bradford GP Specialty Training Scheme.

“If we really want to get to grips with the ‘Child Health’ part of the ‘RCPCH’ title then we all as paediatricians have to redouble our commitment to it. We have to keep telling our community leaders that this is something that we believe in. One area to build up is our inter-sectoral collaboration so when we’re advocating, we are not doing it alone or just with the children and families we are connected with. Let’s do it together with colleagues and professionals from across education, social care, across the child justice system, and across the poverty alleviation sector. Let’s do it together.

Child health and wellbeing isn’t just about health professionals. We need real-time mapping of what is happening in children’s lives. These troubles were clear during the pandemic – we just didn’t know where children were, what they were doing and what was going on in our hospitals, schools, and in homes across the country. It was an extremely challenging unprecedented time, but we can do better next time.

Let’s confront barriers between primary care, secondary care, the community, and services for mental health for children. Nothing that we should be doing should be playing into that narrative of siloed working as a profession, and as paediatricians we need to be working across all of these areas of health and confronting barriers within our own health sector.”

Dr Sunil Bhopal

Sub-specialty Registrar in Community Child Health, Northern School of Paediatrics

Clinical Lecturer in Population Health Paediatrics, Newcastle University Population Health Sciences Institute

Honorary Assistant Professor, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

"When you put up a high enough goal, with enough urgency behind it, you get a coalition of the willing drawn from all sectors"

Smart policy making and service delivery

“What motivates me is facing individual patients and thinking why is this patient having to go through all of this in order to get specialist healthcare? Why is this child becoming sick and ending up on the ward before a specialist shows them how to use an inhaler properly? When I started working with GP’s, I saw that if you bring paediatricians and GP’s closer together and get them working collaboratively you can have an almost perfect system where you utilise resources in a much more connected way. You start to see GP’s getting early notice of a child who is unwell with a mental health problem and they know who to turn to because they’ve actually met a local CAMHS professional and they understand how CAMHS operate, what the thresholds are and how to do things early before things get more concerning. I now go into a GP practice and they ask; ‘who are your children and how can I help?’

There are lots of people who feel the same way. I am part of a group who run training in integrated care for paediatricians, GP’s and other health professionals – the Programme for Integrated Child Health. We are not alone and young clinicians are motivated to do things differently – trainees who enrol are asking ‘please let’s change things’. If you want to do the right thing, you will do everything (focus on social determinants, integrated care etc.) and not just do what the system tells you to do. Co-production is key and supporting GPs who are at the heart of healthcare – a natural ‘node’ in the system – is the right thing. Working with GPs means you immediately start thinking about social determinants and working in a population health way. GPs understand their population; they know their families; they know the housing estate; GPs are connected in a way that we specialists are not. If we just focus on doing the right thing, we actually end up doing things differently, with outcomes that matter.”

Dr Mando Watson

General Paediatric Consultant at Imperial College Healthcare and Clinical Director at Central London Community Healthcare.

Co-chair of the Children’s Executive of North West London’s Integrated Care System and co-founder of the Programme for Integrated Child Health

“Part of my role is to be a system leader and task the expertise that exists and resides within an acute hospital out into the communities that we serve. By doing so, we can illicit much more impact than we would otherwise make by just residing within an organisation that considers its principal role as fixing and repairing people. Born in Bradford represents a really rich repository of information that’s hugely influential and pivotal in our consideration of what Bradford District and Craven and the people of that community need. It also validates a lot of the things we thought we knew about the determinants of childhood and adult disease.

It is not just about the data, it’s also about the relationships that have constructed over time as a consequence of the study – it has become a vehicle and a stimulus of co-production and co-design with those children and their families. There’s a huge unmet level of need amongst the children of Bradford and knowing what those needs are helps us to strategically shape and develop services that can better respond. For example, we know we have double the rate of children with congenital heart abnormality in our city compared to other cities. Knowing that has been pivotal to putting forward the case for more tertiary paediatric cardiology services in West Yorkshire.

It helps us in targeting our communities where the needs are the highest, where vulnerability is the highest, and where the propensity for ill health is the highest. Whether it is by index for multiple deprivation that we shape our services or from the information that the Born in Bradford study gives us, the continuity of care in our maternity services is able to target the most vulnerable women and babies in our communities and enabled interventions at the earliest pre- and post-natal stages to give those children the most positive start.

At the place level, it is also constantly weaving into our plans and discussions among all professional groups as to how we tackle the seemingly intractable problem that we have of health inequalities and poor health outcomes. Along one bus route in our region, there is a 20-year difference in healthy life expectancy as it travels between one of our most affluent areas in the north and Inner-City Bradford – every stop speaks to a reduction of around five years in healthy life expectancy. We need to take this as an impetus and motivation for change, and a catalyst for us collectively as a health and social care system to seek to address these health inequalities. Where better to start than with serving better, in a more proactive and organised way, the babies, children and young people of our district.”

Prof Mel Pickup

Chief Executive Officer of Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Honorary Professor at the University of Bradford

“Where there’s a will, there’s a way. But where there isn’t a will, we need to recognise that there’s just a load of excuses. The pandemic has shone a light on health inequalities that can affect the lives of children and young people, but it’s not telling us anything we didn’t already know. So maybe we should ask why haven’t we done something about this already?

Number one? “Money”. It’s often near the top of everyone’s list of excuses. Maybe we’re worried about double-running costs, maintaining existing services while we “left-shift” into the community, or maybe someone else has the money. Local authorities have responsibility for public health – shouldn’t they fix the problem? We do love a good silo. The truth is, there is never enough money and there probably never will be so we need to work with our partners in our local places to build trust and find ways to share risks, because when you all sink or swim together, it’s a very powerful incentive to do the right thing.

Another favourite that we like to blame is “targets” for giving us perverse incentives. One reason it’s hard to change the model of care is because even when we hit the targets, we might be missing the point, so we can get a gold star for treating a respiratory condition in a timely way, but then we don’t get anything for helping to sort out poor air quality inside or outside the child’s home that caused the problem in the first place. NHS Trusts and Health Boards will naturally spend more time talking about the quality of care they deliver and their performance data, than they do talking about wider determinants of health. It’s not because they don’t care or don’t understand, but because they too have to respond to the external prompts they’re getting and how they are judged and measured.

We could be forgiven for thinking it’s all too difficult. In many ways that is the biggest challenge to developing a new model of care to tackle inequality. We see the scale of the problem and all the obstacles, and any change that’s hard to make is a distraction when we’re all extremely busy. But where there’s a will there’s a way, and now is exactly the right time to be having this conversation if we want to make change.

If you start with the money: tariff-based payments are largely history now in the NHS and it was always possible to introduce local modifications if you agreed locally that was the right thing to do. In West Yorkshire, our Integrated Care System means we’ll have more freedom in the way we manage local performance, with a focus on doing the right thing and to encourage all of us to work together. In Bradford, we have an ‘Act as One’ initiative – it’s amazing how a very small geography can have so many fences and boundaries but already we are getting rid of the many historical barriers. Every single one of our local ‘Act as One’ programmes has an explicit focus on tackling health inequalities and there are great examples around the world that we borrow from, showing the difference it makes when large institutions recognise their responsibility to be anchors in their community and use their influence.

‘Well Bradford’, is a partnership with the hospital, Council and Commissioners, investing in community projects and creating green spaces and healthy places. Born in Bradford and the intelligence this gives us enables us to adopt a targeted approach, so it’s less expensive and risky to make changes to the way we work and we can tailor our models of care for maximum impact. A “manifesto for change” or a “statement of policy” won’t by itself overcome the challenges, but where there’s a will there’s a way, and it sends a really important signal that it is possible.”

John Holden

Deputy Chief Executive Officer and Lead for Strategy at Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

“From that very early stage of a child’s life, it’s really important that health services are available to support a child’s development and for me, it’s about positive relationships between the education and health sector. Being a school leader, we recognise every child has a right to attend school and surely every child has the right to access the right health services, at the right time. A school is often the constant – if every child has to go to school, then health services need to use schools better. We’re already stretched, as with many colleagues in the health service, but this is about ensuring children, who will be the adults of the future, get barriers to health removed and access to services they need from the very earliest bond.

We can support parents to access the right support and agree the necessary solutions for their child – the link between homes, parents and health is the school. Schools are the constant and a key part of the jigsaw and we all recognise that when there is early identification, early support, then we can see children blossom. The key is building positive relationships between health, homes and schools. Schools want the best health provision, this is the same as health professionals and just as much as the parent, who wants the best for their child. It would be of real benefit to the school system if we can build links with paediatricians, GPs and allied health professionals so we can proactively breakdown health barriers, share learning and address any health issues for children and young people.”

Daniel Copley

Executive Headteacher of St Cuthbert and The First Martyrs’ Catholic Primary School, Bradford

“A lot of the work I’ve been doing over the past 10 years in Wessex has been to integrate services for children and young people. To achieve this, I’ve worked with colleagues from health and social care across a large geographical footprint and it’s fascinating how much we can all resonate with each other – there’s a huge amount of passion amongst paediatricians for the role that we can play. I think first and foremost we have to believe that we can influence the way that care is delivered for children and young people, but often we feel that we just work within a system that we have very little ability to change. Most paediatricians only work within hospital-based settings, which makes it harder for them to have an overview of the entire system involved in the health and wellbeing of children; as a start we need trainees to see things through a wider lens.

Achieving change requires a political savviness that sometimes we as paediatricians don’t have. We are hugely passionate about delivering care for children, but unfortunately we sometimes struggle to convince the people that fund services that the way we care for children and families need to be improved. To address this, we need to understand the current commissioning landscape and realise that if we don’t have a seat of that table, we’re not going to influence change. We have to get ourselves in that position and ensure that paediatrics has a voice within the Integrated Care Systems.

We also have to be realistic. Influencing how social care is delivered, especially the really important issues that make a difference to children such as housing, education, and the environment is extremely challenging for anyone involved in whole system working. That’s where relationships are so important, and it takes time to build those relationships. Taking the time to build them properly is paramount if we are to influence and improve wellbeing of children in the long term.