Module 1 – Starting Your Quality Improvement Journey

In collaboration with QIClearn, the first of our micro-QI online modules introduces healthcare professionals to quality improvement methodology and shares how paediatric trainees have explored QI across different levels of the RCPCH Progress Curriculum.

Welcome to Quality Improvement!

At QIClearn we support paediatricians as they take their first steps in quality improvement, and even more. In the past 4 years we have seen over a hundred paediatric trainees complete their first QI journey from start to finish. Most of these have recorded their journey in a poster and many have shared their work at international conferences.

Learning how to improve using a robust change method is a skill we can take with us throughout our career. So starting small and growing these skills alongside our clinical training is a great investment for our future and that of our patients too.

In this short module we will:

- Set the scene by considering the four sciences that we draw on in our day to day work

- Consider how quality improvement methods sit alongside other techniques that support quality and safety such as audit and research

- Look at how quality improvement processes mirror those of clinical processes

- See how paediatric trainees explore QI within different levels of the RCPCH Progress Curriculum

- Gain insight into acquiring an improvement mindset

This module is led by Nikki Davey, a Quality Improvement Practitioner and Coach. Nikki has a long association of working with paediatricians through her work in patient safety over many years. She founded the Quality Improvement Clinic in 2013 and has designed and delivered training to 1000’s of people since then. Through QIClearn, her company offers digital, virtual and blended programmes. Nikki is also a Trustee and longstanding supporter of the Clinical Human Factors Group who campaign for the adoption of human factors principles to make healthcare a safer place.

The Four Sciences

In this video clip Nikki Davey considers what we can learn from science to make healthcare safer and more efficient.

After you’ve watched it you might want to think about your own journey through the sciences and which ones you want to enrich.

Improving quality in healthcare

Since the NHS was created, a range of approaches have been used to improve the care that is given. In the early days, audit and research were the most commonly used approaches. As the number of effective interventions developed and the ways in which they could be delivered increased, audit became more clinically focused, research informed evidence based medicine and service evaluation was added into the mix. More recently we have begun to explore disciplines developed and used successfully in other industries such as transformation and quality improvement. The diagram below gives an overview of how Adam Backhouse and Fatai Ogunlayi have described the relationships between these 5 approaches:

Clinical audit provides assurance that people are adhering to an agreed standard of practice. It can usefully identify gaps between current practice and agreed best practice. However, audit reflects only what is happening at a particular point in time, and does not usually reflect the variation that occurs from week to week, day to day, or patient to patient. Furthermore there is a tendency for the audit cycle to end with recommendations for closing the gap by leaving a list of recommendations to be fulfilled by someone else who may not know or have been involved yet. This audit gap is one place you can start from when starting out on a quality improvement project:

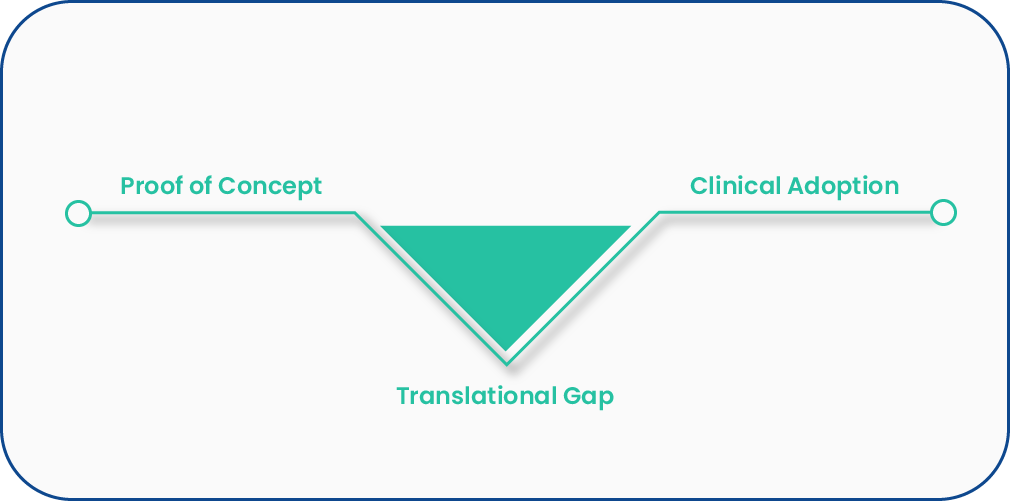

Research underpins many modern day healthcare treatments. The gold standard is considered to be randomised controlled trials, and whilst this is a systematic and rigorous way to answer important questions about efficacy and effectiveness or treatments, such trials do not answer all of our questions. Controlling other variables in order to isolate the effect of the item under investigation, often means excluding large parts of the population and this means effects that are detected may not be universal, or may not be realised when conditions vary significantly from the study setting, population or health facility. Translational research is seen as one way that we can close the gap between research and practice.

Service evaluation explores the effectiveness or efficiency of a service in order to inform local decisions about it. It considers issues that are broader than quality, but are often directly or indirectly linked to quality e.g. workforce, financial viability, demand, sustainability, demand. As with audit, it reflects a point in time and may not accurately represent the variation that is commonly present in most service provision, but it may identify risks associated with change and attitudes to change. In this way it may be a catalyst for change in its own right.

Transformation is a deliberate and planned process that sets out to effect dramatic and irreversible change in the way a service is delivered. It usually occurs on a large scale. In our lives we’ve seen this play out through transformational technologies such as the internet, mobile phones, and messaging apps. Clinically we’ve seen this with non-invasive surgery and standardised monitoring for some clinical conditions. Whilst clinical transformation is often driven by technology, it is worth noting that it took a pandemic for healthcare to embrace technology that has been around for many years to make virtual consultations the new norm.

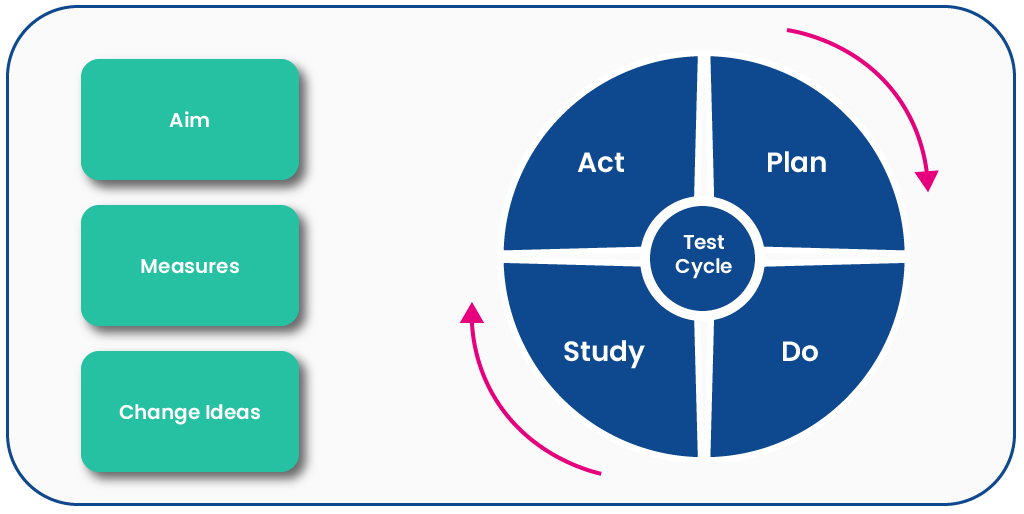

Quality improvement is based on learning and continuous improvement. As a change method it is increasingly recognised as having something to offer healthcare. It works in the gaps that we often find in audit and in translating research into practice. The methods are both people and systems focused, appreciating the psychology of change and using data to help us understand what is happening in the system and whether changes have occurred. The many small changes that are required for a big change to occur are often within reach of the people who deliver care. Their expertise and insights of work as it is, rather than work as imagined allows the adaption required to spread good practice across systems that differ significantly.

How QI mirrors your clinical journey

Most of us acquire new skills everyday and yet none of us become great at anything overnight. Instead we build from being a novice to becoming more accomplished over a period of time.

This is the same whether we are considering clinical skills or improvement skills, and yet somehow the latter, with its novel language can seem more of a challenge.

In this short video, Nikki Davey draws a parallel between the process of treating patients and the process of generating improvement:

Progress your QI

As we’ve suggested already, quality improvement is a mindset and a set of skills that you can develop and take with you throughout your career. This is increasingly recognised in clinical training and for paediatricians in particular in Domain 8 of the RCPCH Progress Curriculum.

The ambition is that by progressing over time everyone independently applies knowledge of quality improvement processes to undertake projects and audits to improve clinical effectiveness, patient safety and patient experience; Identifies quality improvement opportunities; Leads and facilitates reflective evaluation in relation to quality improvement interventions.

And if you still need a little convincing, or want some inspiration, why not listen to some people who have come across QI at different times in their training, and hear what they have to say about it:

Dr Georgina Ndukwe has just begun her specialist paediatric training, hear her talk about her experience as she begins her first steps on her QI journey:

Dr Segn Nedd produced an accomplished piece of improvement work for her first full QI experience, for which she has won prizes! Segn now shares her work as often as she can and hopes that it will inspire others to learn about QI:

When Dr Kiran Rahim came to QI as an ST2 it was a revelation to discover that QI was not in fact the same as audit. Here she describes how this realisation helped her deliver an improvement that was sustained after she had moved on through several training rotations. Since then she has gone on to complete many more QI projects and is leading and teaching others to use QI to improve services for the patients they care for:

Developing an improvement mindset

In this introductory module we’ve given you some insights that we hope will be helpful to you, and whilst concepts and theories that underpin change and improvement are essential, you will gather from hearing from Georgina, Kiran and Segn that developing an improvement mindset goes far beyond the ability to memorise a model of change.

When we talk about learning we are particularly interested in the time invested in action and experience, rather than your ability to memorise a model.

The good news is that we have all had experience of an improvement mindset as children. If you want to know more about this, listen to Professor Don Berwick illustrating this through his stories at the International Forum on Quality and Safety in Healthcare in 2015 (3.46mins to 8.54mins):

Module 1 reflection

Next steps

Further reading

Backhouse A, Ogunlayi F. Quality improvement into practice. BMJ 2020; 368 :m865 doi:10.1136/bmj.m865

QIClearn courses

Module 2 - An Introduction to Improvement Science

Learning how to improve using a robust change method is a skill we can take with us throughout our career. This second module in the QI series explores the science that underpins improvement, the challenges of starting small, and delves deeper into diagnostics and improvement methodology.

Go to Module 2