‘Keeping Sick Children Out of Hospital’- The Ambulatory Care Experience (ACE) service

Developing a standard ambulatory care model for managing acute illness in children and young people at home.

The initial problem and its impact

In Bradford, Children and Young People (CYP) account for 30 per cent of Emergency Department (ED) assessments and 90 per cent of medical patients are discharged home after initial assessment or a period of observation. Only 10 per cent of patients seen are eventually admitted to a hospital bed. This suggests that they could have been managed in a different way and in a different environment.

The majority of presentations are due to conditions like asthma, viral wheeze, upper respiratory tract illness, gastroenteritis or fever due to viral infections. In Bradford we see around 37,500 CYP each year in our ED; 35-40 per cent for medical reasons. For CYP attending ED each year this equates to a potential of 13,500 people each year being managed in a different way.

Nationally the figures are very similar. A recent review of emergency admissions in London showed that approximately 45 per cent of children seen in ED needed an observation period of less than 12 hours and only 10 per cent required a hospital admission.

Over the last 10 years there has been a 30 per cent increase in the number of under 5 year olds coming to ED. This compares to an increase of 15 per cent for all CYP seeking urgent care over the same time period. These figures are due to a changing demographic and a change in carer behaviour for several reasons. The lack of paediatric experience in primary care also plays a role in increasing referral rates to secondary care services.

In paediatrics, interest in a ‘virtual hospital’ care model is increasing as acute trusts struggle to manage the pressures of this increasing demand, resolute ED targets and a reduction in acute paediatric inpatient beds. The cost of looking after a CYP in hospital is also ten times more expensive than care provided in the community.

Many national policy initiatives like the NHS Five Year Forward View and the Keogh Urgent and Emergency Care Review to streamline urgent care provision have focused mainly on adult urgent care services. However across the country paediatric ambulatory urgent care (defined as the provision of same day care for children and young people who would otherwise be considered for an emergency admission) is gaining traction. It is consistent with the RCPCH Facing the Future Standards policy document.

There is now a significant opportunity to change the urgent care pathway for CYP and to provide much of this care at home. Home is where children feel most safe and relaxed. Hospital admissions are also very costly for families in many ways.

Causes of the Problem

At present when a CYP becomes unwell and needs to see a clinician they usually:

- go to see their GP

- attend a walk in centre, or

- attend ED

In most cases when they attend their GP surgery they are either:

- seen, treated and discharged with advice, or

- seen and referred to hospital

In hospital or walk in centres they are usually:

- seen, treated and discharged home with advice

- seen and observed for a few hours, or

- seen and referred to the paediatric team.

The paediatric team, after assessing the CYP, have the option of:

- discharging the CYP

- arranging an admission for a few hours of observation, or

- arranging an admission for a longer period

The CYP pathway is often rigid and influenced by a number of factors that are difficult to control. This includes the presence of key decision makers with experience in paediatrics, the acuity of cases at any given time and the demand and capacity in the surgery or department. Unsurprisingly outcomes are variable.

There are several paediatric urgent ambulatory care (PUAC) models around the country trying to deal with various aspects of this complex care pathway. Each delivers good care to their local population. Each model is slightly different with different components and governance processes. Most have been internally evaluated with generally good patient and family satisfaction, when this has been measured.

Quantitative evaluations of these services have been extremely difficult and most evaluations to date in this field have been qualitative. Most teams have taken a pragmatic approach to address their local need often based around local commissioning preferences and negotiation. It has been difficult therefore for services in one area to adopt the model of another area.

In PUAC, the development of innovative shared system wide clinical pathways for high volume conditions, the use of new technologies, rapidly accessible diagnostics and new models of care coupled with developments in the NHS workforce now allow a real opportunity for close collaboration between community and secondary care services. These innovations are providing urgent care outside of the traditional secondary care settings, sometimes even in the CYP’s own home. This allows tailoring of services to patient needs while preserving hospital beds for those who need it most.

In Yorkshire, acute trusts have developed their urgent care services independently of each other. This means that management pathways and models of care for common high volume conditions like asthma vary significantly between local trusts despite standard national guidance. This inevitably results in inefficiencies and there is currently no process for shared learning and quality improvement even amongst neighbouring trusts. There is currently no mechanism to collaborate across districts, counties and beyond.

Project Aim Statement

In Bradford there is a shared vision across the health system that ‘the key to delivering effective emergency and urgent care is ensuring that the whole system is designed to support self-care and community care at home, thereby reducing avoidable hospital admissions and facilitating timely early discharges’ – Institute for Innovation and Improvement.

Our overall aim is to produce a standard model for managing acute illness in CYP that can be adopted by other trusts. The model will target the 90 per cent of CYP currently coming into secondary care services who require a period of observation but not an admission.

Specific:

- We will develop an acute care model that will produce a more streamlined and quality acute service that is safe, timely, equitable, effective efficient and child and family centred.

- We will produce 5 clinical pathways over a 12 months period that will be used in this new model.

- The model and pathways will be designed in such a way that they can be used ‘off the shelf’ in all acute trusts in the UK. This will include standard governance processes and a bespoke training programme.

- The model will be easy to adopt and be delivered within 1 year of commissioning.

Measurable:

- The new model will be developed with families and agreed by clinicians in primary and secondary care.

- We will produce our first 5 pathways in 12 months from launch. These pathways will be developed and agreed across primary and secondary care. Each will contain a referral crib sheet (with inclusion and exclusion criteria and safety netting advice), a care bundle and a patient leaflet.

- We will produce each pathway in a standard format within an implementation framework. This will include i) a nurse training programme ii) a process to assess new clinical pathways against ‘current state’ to ensure safety iii) a process to audit the pathway after implementation to see if changes are required to the pathway. We will develop standard governance processes that will include –procedures for clinical escalation, standardised communication, full capacity protocols and also how to manage families who cannot be contacted after referral.

- The service will be developed within 12 months of commissioning.

Achievable, Realistic and Time Limited

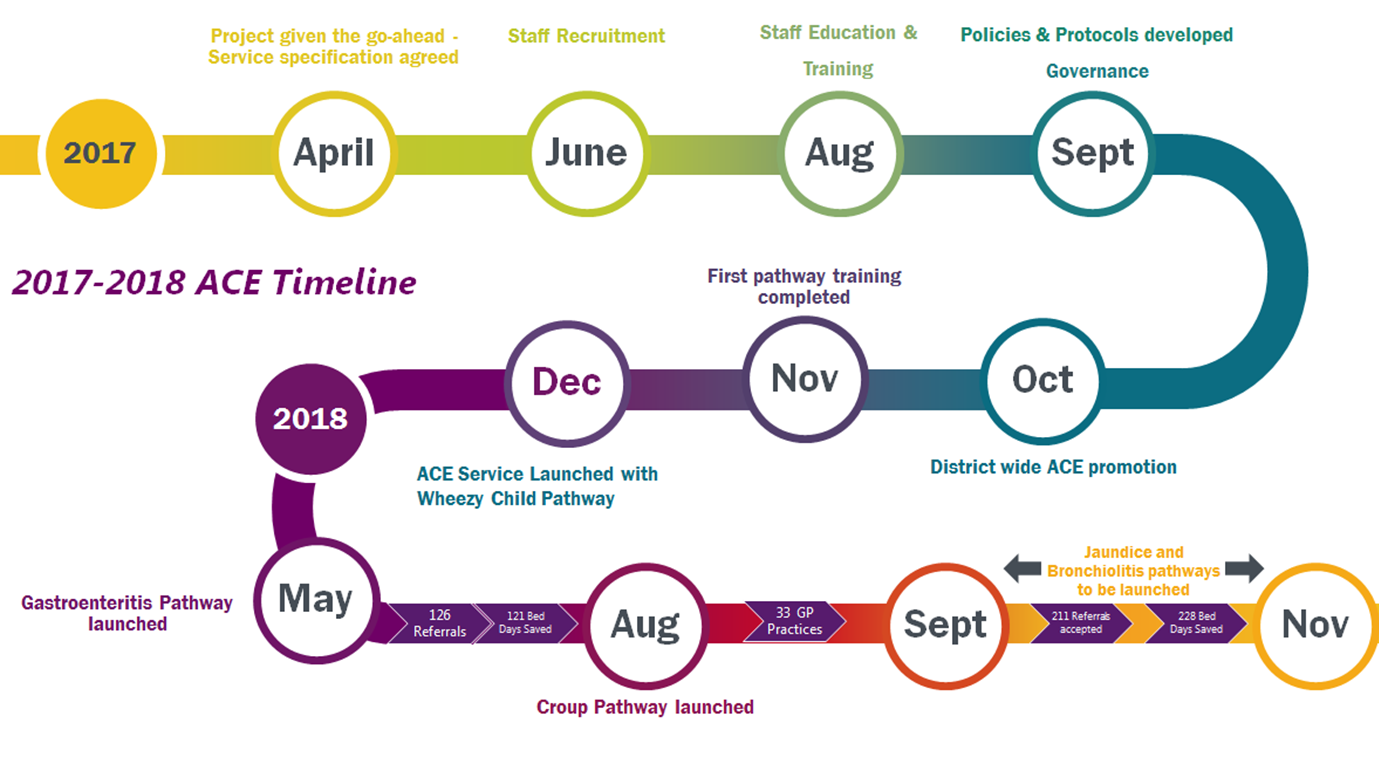

The project is currently running to our implementation timetable:

Stakeholders

ACE Clinical Lead: Dr Mathew Mathai oversees 4 work streams – i) clinical governance, ii) service configuration, development and implementation, iii) pathway development, iv) training and competence.

ACE Project manager: Denise Stewart manages the ACE implementation programme.

Trust Management: Prof Clive Kay, Chief Executive; John Holden, Director of Strategy; Cindy Fedell Director of Informatics; Dr Janet Wright Directorate Lead, and Dr Helen Jepps and Dr Shaun Gorman, Service leads.

Clinical Commissioning Group lead for Acute and Urgent Care: Dr David Tatham keeps the CCG Urgent Care Board informed of project development.

Lead commissioner for Urgent Care: Louise Atherton.

Primary care: Dr David Tatham is the CCG lead for Acute and Urgent Care in Bradford. He is also a GP. He leads on the development of the primary care section of each clinical pathway. He also leads on promoting the service and pathways in primary care.

GP Surgeries and Primary Care Advanced Nurse Practitioners: The service is open to referrals from all surgeries across Bradford.

Inpatient ward staff at BTHFT: This includes ED and the Paediatric Clinical Decision Area and includes doctors, nurses and the administrative team. The team are updated on each pathway. Hospital doctors and Advanced Nurse Practitioners (ANP) can also refer into the service. Consultant Paediatricians take full clinical responsibility for all CYP referred into the service. Together with the ED ACE leads (Drs Liz Jones and Georgina Hudson) they have been involved in developing governance processes and input into the development of all pathways. They are involved in training ACE nurses and assessing their clinical competence.

Head of Children’s Nursing at BTHFT and lead for ACE clinical governance: Kay Rushforth.

Children’s Matron at BTHFT for community service: Emma Wilkinson manages the ACE nursing team.

ACE nursing team: Each ACE nurse inputs into a clinical pathway and helps to develop it. Each ACE nurse is also linked to individual GP surgeries, to Consultants and to specific clinical areas (i.e. primary care, ED and Paediatrics) for service promotion and networking.

Children and Family: We engage with CYP and families through specific sessions including focus groups and also through paper and online questionnaires.

Team administrator: Attia Gilani produces real time reports on all aspects of the service including Key Performance Indicators. These are fed back to Commissioners on a monthly basis.

Clinical educators and training development: Dawn Hare (ANP), Tamlin Walker, Laura Deery and Clair-Marie Clarke have developed a training package for ACE nurses.

ACE nurse supervisors: Dr Liz Jones, Vicki O’Keefe (ANP), Sharon Popple (ANP), Gill Falloon (ANP), Dawn Hare (ANP), Dr Anne Pinches, and Dr Mathew Mathai.

Pharmacist: Manrita Khatker leads on medicine governance for each pathway.

Pathway lead developers: Dr Anne Pinches, Dr Uma Jegathasan, Dr Helen Berry, Dr Anil Shenoy, Dr Sumera Farooq, Dr David Tatham and Dr Mathew Mathai.

Web development: Dan Webber has developed our webpage and keeps it up to date. He is also involved in analysing our on line patient experience surveys. IT support: Steve Pearson and John Greenaway.

Bradford Institute of Health Research and Improvement Academy collaboration: Prof John Wright and Beverley Slater. York University are undertaking an external service evaluation sponsored by Connected Health Cities Yorkshire and Humber.

Health Education England: Funded a Clinical Leadership Fellow to develop a local network CYP Ambulatory care across West Yorkshire in 2019-20.

The King’s Fund: Dr Mathew Mathai has a blog on their website promoting the ‘virtual hospital model’.

New partnerships are being sought with Yorkshire Ambulance Service, clinical prescribers and NHS 111. Initial scoping meetings have taken place or are currently being planned.

PDSA Cycles / Solution(s) Tested

With reference to the specific aims above:

- The Ambulatory Care Experience (ACE) model is the result of system wide collaboration between GPs, the local CCG and the Bradford Royal Infirmary (BRI). The service which is the first of its kind in the UK, provides specialist nursing care at home for unwell CYP who would ordinarily have been referred, seen and potentially admitted to hospital. Referrals into the service are taken from primary care, ED and the CYP Clinical Decision Area (CDA) at the BRI. ACE is delivered in the community setting and is staffed by children’s community nurses (band 6) working between 09.00 – 21.00, 7 days a week.

- Once a CYP has been accepted into the service full clinical responsibility lies with the Consultant Paediatrician on call at the BRI. CYP have 24-hour ‘open access’ to the CDA while under the ACE service. If a CYP meets the pathway referral criteria they are accepted into ACE. Referrals are made by phone and electronically via primary and secondary care electronic patient systems. The ACE nurse then makes telephone contact with the family within 2 hours and arranges a home visit usually within 4 hours of referral. At this visit a focussed history and assessment is undertaken. Further home visits or telephone reviews are then arranged.

- CYP remain in the service for up to 3 days. In addition to acute management the team also deliver a ‘care bundle’ e.g. for asthma/wheeze this includes support with inhaler delivery, monitoring effectiveness of treatment, education in managing future episodes, identifying deterioration and smoking cessation advice. Nurses discuss each CYP under their care with the paediatric consultant. Clinical discussions occur between the ACE nurse and consultant at least 3 times a day.

- Individual clinical pathways have been developed with GPs, nurse practitioners, nurses, pharmacists and paediatricians and are based on best available evidence, national guidance and local clinical agreement. To date we have implemented the asthma/ wheezy child pathway, the gastroenteritis pathway and the croup pathway. The bronchiolitis pathway and neonatal jaundice pathway will be introduced by the end of December 2018.

- Pathways have been developed with a multidisciplinary team and according to a tightly managed implementation process. Each pathway has been audited against ‘current state’ (before launch) to ensure safety and then re-audited after ‘go live’ to make sure parameters are appropriate and there are no quality issues.

- The model and pathways are based on a simple design with components that can be found in all acute trusts around the country. Governance processes have been developed and tested and in the first 9 months there have been no adverse events.

The model and pathways have all been implemented to a time frame.

Data results

Main outcomes in the first 9 months of the service

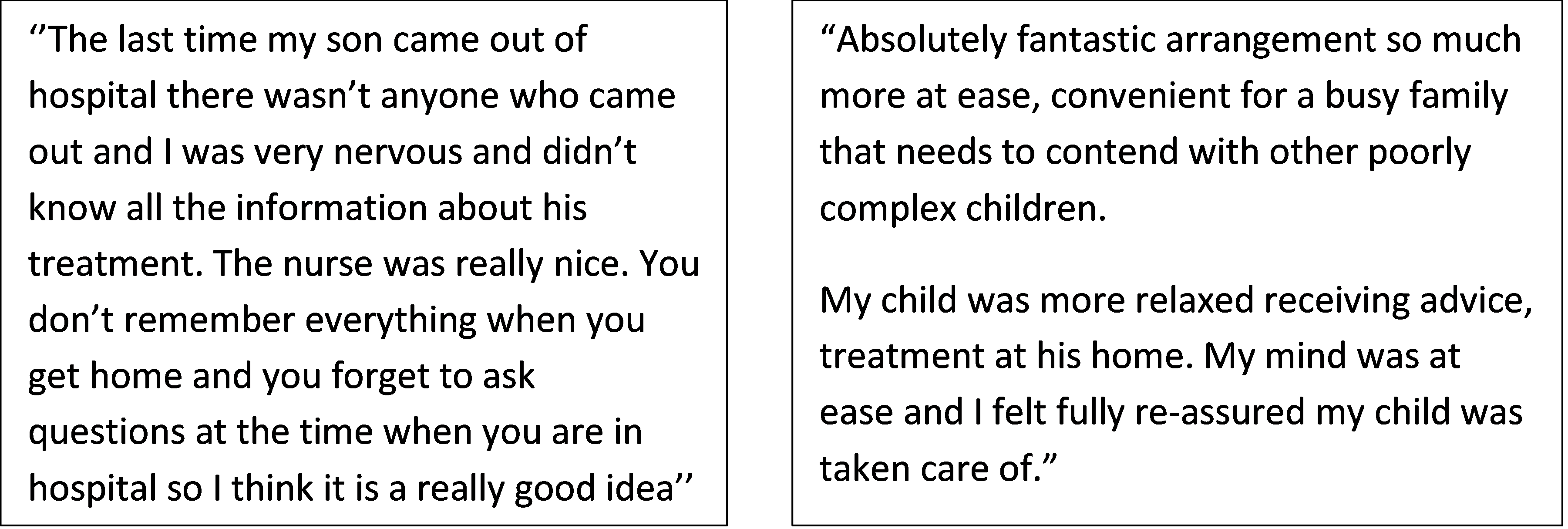

100 per cent of those responding to the service user satisfaction survey said they were very happy with the service.

Some responses:

There have been no adverse events since service launch.

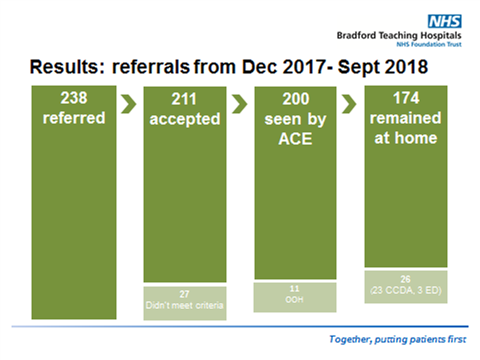

In the first 9 months of the service 87 per cent of appropriately referred CYP referred during service hours had all their care delivered at home.

Service model and Key Performance Indicators (KPI):

KPI1 – Achieve a minimum of 6 contacts each day.

- This was achieved on 17 per cent of days. As a new service we were keen to develop safely. Therefore we implemented one pathway initially and tested all our governance processes around it. We then launched the second pathway six months later. We have developed an engagement strategy to address this KPI.

KPI2 – Accept 100 per cent of appropriate referrals.

- 95.5 per cent of appropriate referrals were accepted. The cases not accepted were due to service capacity and referral times. The team followed the escalation protocol successfully.

KPI3 – Make contact with 100 per cent of families within 2 hours of referral.

- This was achieved 98.5 per cent of the time. The only family that we were unable to contact did not have a working mobile. They were seen within 4 hours of referral. The team followed the governance protocol successfully.

KPI4 – 100 per cent access to consultant/step up huddles.

- This was achieved 100 per cent of the time.

KPI5 – 100 per cent of patients have a face to face review in the home.

- This was achieved 98 per cent of the time. The 2 per cent of CYP who were not seen at home were managed by phone and after discussion with the consultant.

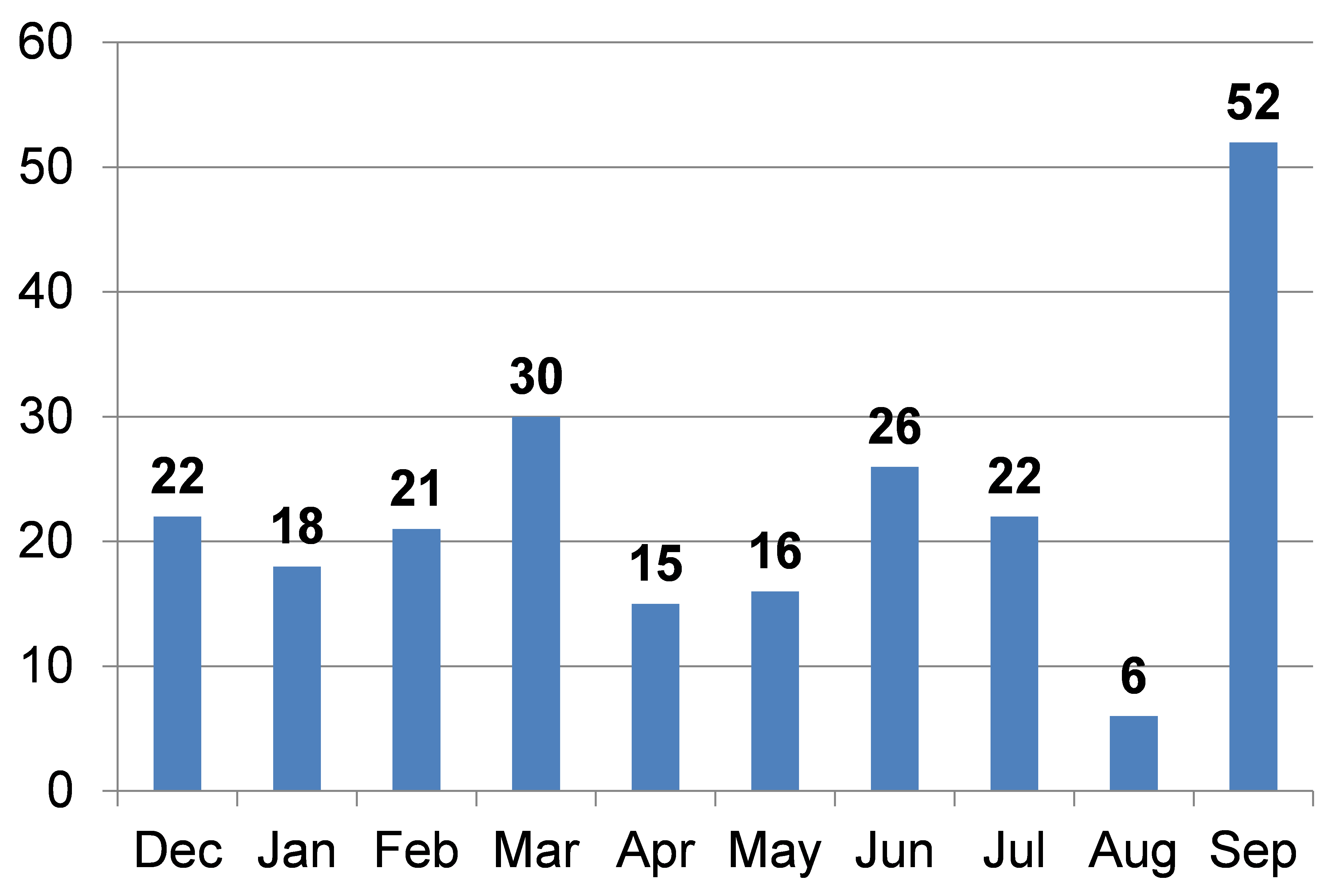

Referral times into the service:

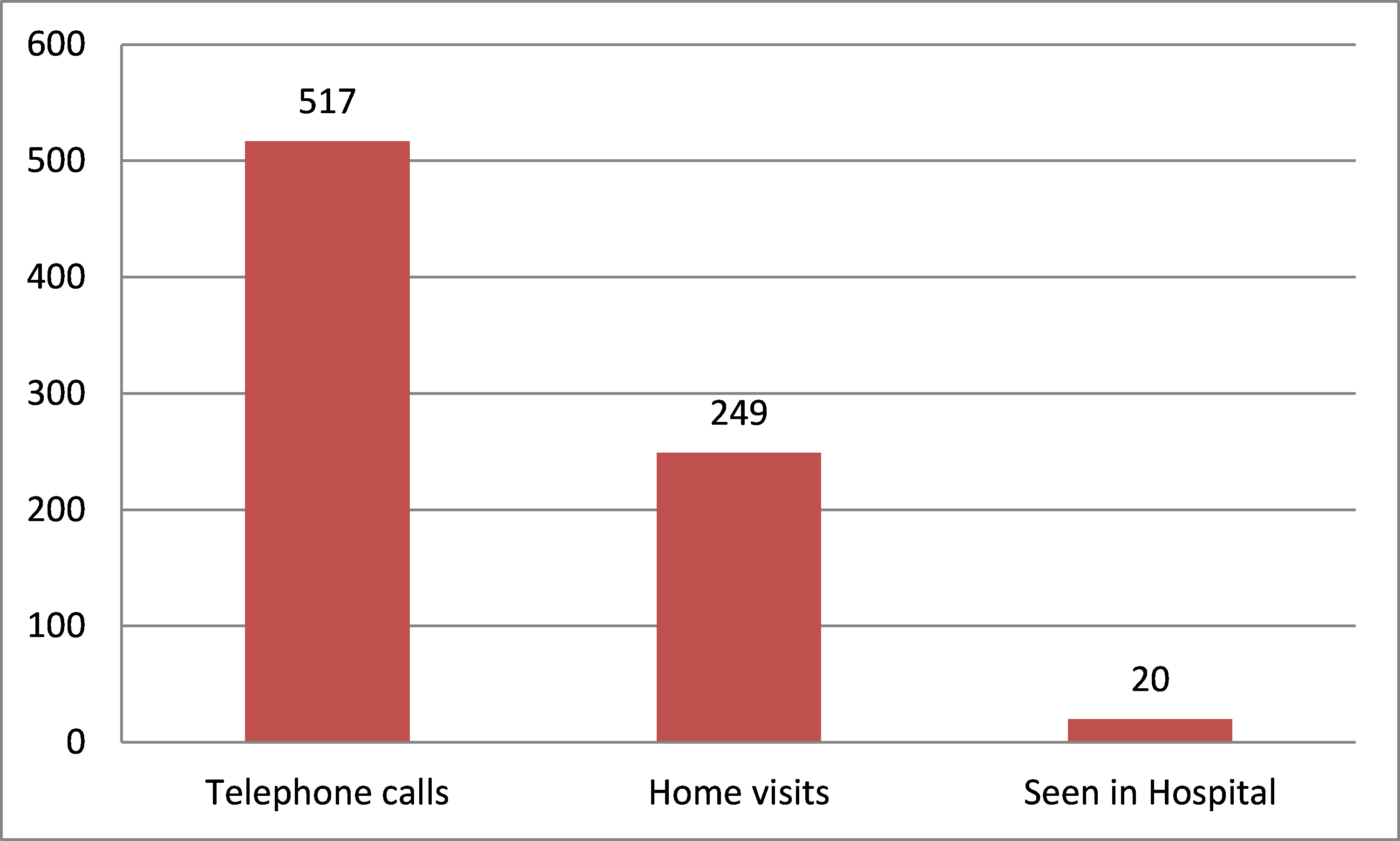

Frequency of ACE mode of contact:

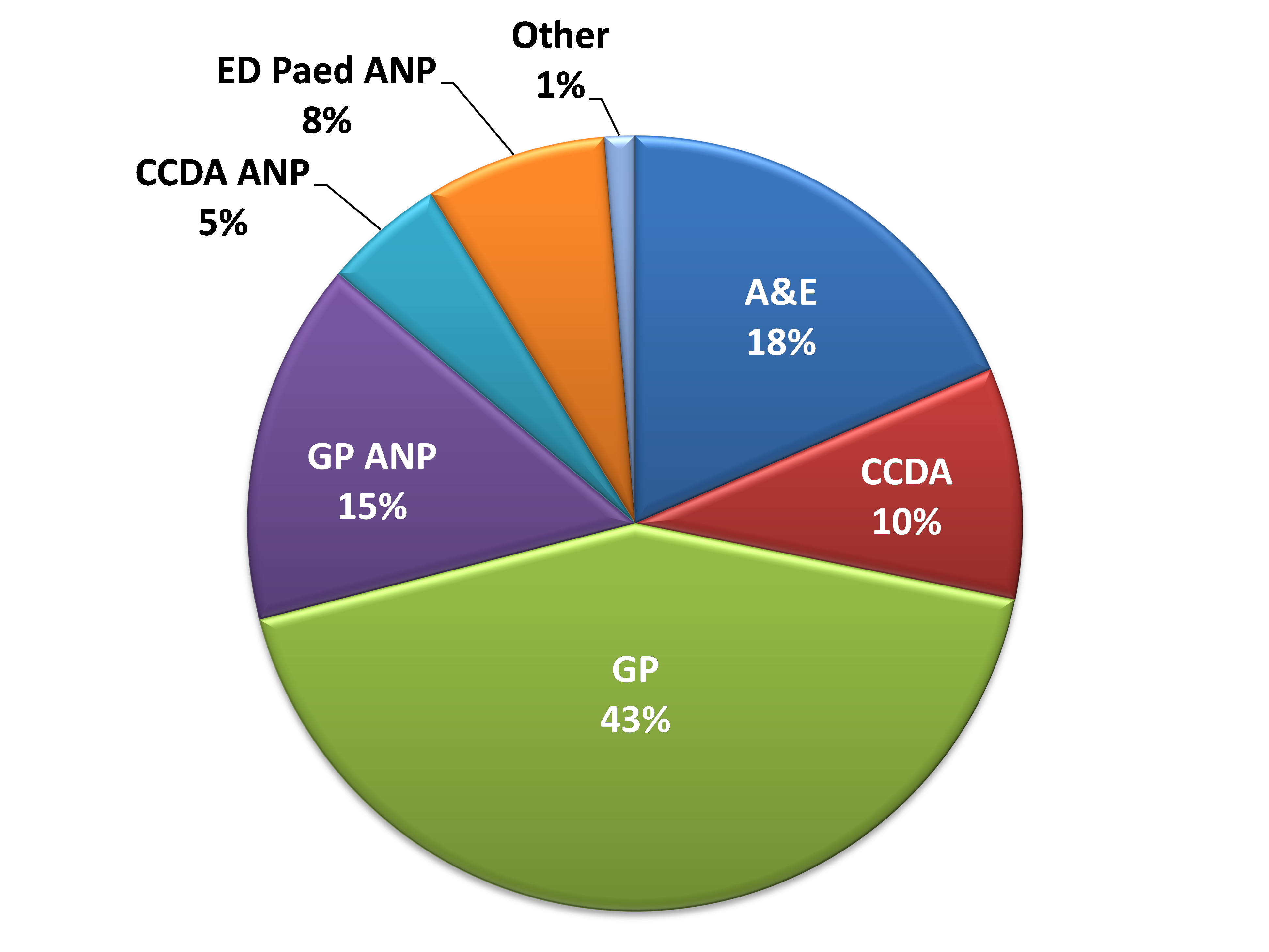

58 per cent of referrals have come from primary care:

34 different GP surgeries have referred into the service (out of a total of 95 surgeries), and we have saved 228 bed days in the first 9 months:

94 per cent of referrals so far have been for just one pathway – the wheezy child.

To maximise the potential impact of the service (i.e. increase our referrals) we will need to work on the ‘pull’ and ‘push’ of the model.

How This Improvement Will Be Sustained

A challenge met by transformation – the ACE service

Twenty-first century healthcare is patient centred, aims to reduce waste and increase value, is based on system working, operates through networks, engages all stakeholders and is driven by knowledge. For ACE to be sustainable we need to embrace all of these values and aims.

Patient centred:

- Engaging families and CYP in coproduction – families and CYP are invited to focus groups and provide feedback on pathways. All our work is centred around the shared vision that ‘the key to delivering effective emergency and urgent care is ensuring that the whole system is designed to support self-care and community care at home, thereby reducing avoidable hospital admissions and facilitating timely early discharges’ from the Institute for Innovation and Improvement.

Reducing waste and increasing value:

- ACE is a tested and quality acute care model. Our initial Quality Improvement work has produced very encouraging results. We have tested the governance processes and the model and pathways are safe. The model has provided standardised, evidence based, consistent specialist care in the home. Each pathway has a care bundle that includes health education and promotion that empowers families to self-manage.

System wide working, operating through networks and engaging stakeholders:

- We are working effectively across the system and developing a number of ACE ‘champions‘ across primary and secondary care. We still need to 1) study barriers to referral from primary and secondary care using focus groups and referrer questionnaires 2) streamline the referral process by working with primary and secondary care IT teams 3) work on how to identify and ‘pull’ appropriate CYP into the service from the current pathway, and improve engagement with referrers by fully implementing our engagement strategy document.

- We need to promote the service in innovative ways, internally through one to one stakeholder meetings, departmental, divisional and Trust meetings and externally via individual GP surgery and GP forum meetings, as well as at local CCGs and STP forums.

- We need to use our social media platforms and webpage more effectively to keep in touch with service users, allowing them to input into service development. We need to have clear outcome measures tracking the success or otherwise of these initiatives.

- We are seeking collaboration with the Yorkshire Paediatric Society and building on early links with Health Education England (who have funded a leadership fellow for 1 year helping us to build an ambulatory care network across W Yorkshire in 2019-20), the RCPCH and King’s Fund to seek partners in this innovative space.

Driven by knowledge – research:

- Projects of this type have mostly been evaluated using qualitative data. However for commissioners to decide on whether an intervention has value and is worth investing in, a quantitative approach would be more compelling. We are working with York University and The Connected Health Cities project, linking primary care and secondary care data in order to study the model and individual clinical pathways. We are now able to more robustly assess whether a system wide intervention such as ACE is really value for patients and value for the wider health economy. Having greater collaboration across a network would give us a unique opportunity to study the service against other care models.

Challenges and Learnings

There have been several key factors in the success of this project:

- A recognition amongst all stakeholders that the status quo was not sustainable.

- An understanding of National, Local and Royal College Policy amongst key stakeholders.

- Development of the service in an acute trust which has championed the concept of a ‘virtual ward’ and has a long term strategy of being ‘short stay by design’.

- A shared vision guiding commissioning and service development.

- A collaborative approach from the start with equal input from community and secondary care services, from commissioners and providers and across the multidisciplinary team.

- A decision to create something of high quality that we would be proud to share with other teams outside of Bradford. We wanted to develop a service that had a simple design and components found in every acute hospital.

- A decision to robustly evaluate the project with an external academic team.

- The development of a project team with several smaller work streams with clear aims and objectives and timelines.

- Development of an overall implementation plan with multiple PDSA cycles that were tightly managed and with a time frame.

- Real time data to guide development.

- A communication strategy for stakeholders.

- A willingness to share success and failure.

- ‘Team time’ – developing and embedding shared values and sense of purpose and sharing positive results regularly through informal and formal meetings.

- Time set aside for project leading and management.

What I would have done differently

There has been some resistance to change. These stakeholders have had different reasons for their position. In future I would explore their concerns more fully and try and address them as early as possible. I would also try and involve them in key stages of project development.

Suggestions For Further Implementation

A national problem with a proposed standardised intervention that is:

- Adaptable

- Replicable

- Can be delivered within a short time frame

The problem of increasing numbers of CYP attending secondary care for acute illness is a national one and has many contributing factors. Data on length of stay and requirement for clinical observation after assessment suggests that only around 10 per cent of CYP require an admission of longer than 1 day. This new service with its new pathways aims to address this by interacting at several points with the current acute care model found across the country.

Several similar projects have been developed around the UK providing excellent care to local populations. ACE was developed for replication and therefore designed to be adaptable with essential parts available in most acute care systems in the UK (i.e. a consultant paediatrician, a trained children’s nurse and a clinical educator). It was also developed so that teams could adapt and develop it for their own acute service.

Development through networks and research

Commissioning decisions should ideally be based on robust clinical data confirming value for money. This data is currently lacking in most interventions and most published evaluations have been qualitative and cost neutral. ACE is a standardised intervention that can be evaluated for value. To do this we have linked in with York University and the Connected health Cities Project to undertake an external evaluation of the service.

Clearly the more units interested in collaborating with us the greater the power of the evaluation. We are hoping to set up a paediatric urgent ambulatory care network in 2019 to help drive this and similar innovations forward. If the service does not provide ‘value’ then as a network we will be able to review each pathway and adapt it and re-evaluate.

Outward facing and collaborative

We have linked in with our local Sustainability and Transformation Plan to look at how the ACE service can be developed across a wider NHS footprint. This next step is key to medium and longer term sustainability and will hopefully be a key driver for greater collaboration locally to help deliver the NHS Long term plan for our population. We are also keen to work with other like-minded units nationally.

For more information please visit our webpage and get in touch!

Project Lead: Dr Mathew Mathai, Consultant Paediatrician

Organisation: Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Published: July 2019